‘He brought it on himself’

By HELEN SCHWAB

When Willie McDaniel’s body was found near his home in 1929, neck broken, the first Charlotte headline was “Mystery Over Death of Negro in Newell.”

But the mystery of Charlotte’s second documented lynching had scarcely begun to unfold.

In coming days, newspapers would report:

- Witnesses testifying that a man threw a rock and aimed a gun at Willie McDaniel during a confrontation, then chased him, gun in hand, hours before his death – a man who confirmed this himself, yet appeared never to figure in police theories of the crime.

- The appearance – then disappearance – of both a possible murder weapon (though usually thought of as hangings, lynchings include other forms of fatal violence) and a letter signed “A White Man” that promised clues to the killing.

- A shocking exhumation, amid questions about McDaniel’s injuries.

- Neighbors recalling the eerily similar discovery of another body, years before, nearby.

Here is a timeline of 140 days in 1929, the most detailed account ever compiled about what happened to Willie McDaniel. It’s based on census, land and genealogical records, and about 50 stories from Charlotte’s two daily newspapers of the time – both owned and edited by white people — and an editorial about the case from one of two Charlotte’s Black-run weekly papers, the only time McDaniel appears in their limited available archives. (You’ll also find links to deeper context, marked in bold-faced gold type; look at more about sources here.)

Willie McDaniel’s was the second of two racial terror lynchings documented in Mecklenburg by the Equal Justice Initiative. There were almost certainly more.

This timeline challenges the newspaper stories and reports, and asks questions about what isn’t in them.

It begins the day of a confrontation between Willie McDaniel and his landlord, Mell Grier.

Confrontation, and a chase

Saturday, June 29, 1929

About noon, on a fair day that will get up to 85 degrees.

Willie McDaniel drives a two-horse wagon up to the house of Mell Grier.

With him is George Hurd. Both are Black men who rent farmland from Grier here in northeast Mecklenburg County, and they’ve come to pick up some flour Grier has brought back from Charlotte.

Six days from now, several people will describe what happens next, to the six white men chosen as a coroner’s jury.

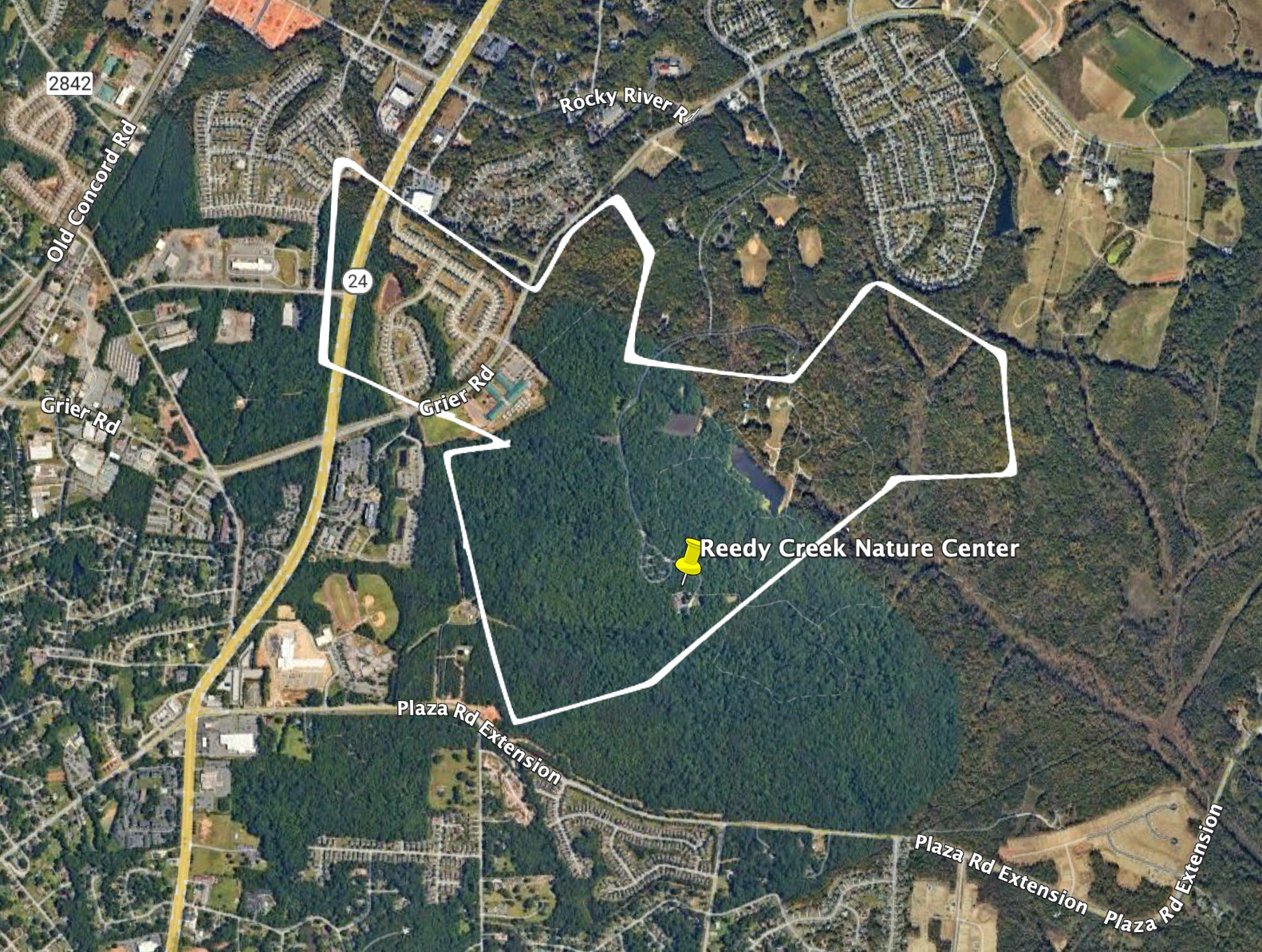

McDaniel, 22, moved earlier this year with his wife, Sallie, from South Carolina – where his family has worked the land since at least 1870 (read about his parents and siblings here) — to Grier’s farm. That land sprawls across about 450 acres of fields, woods and streams connected to Reedy Creek.

Grier, 51, is a prominent white farmer here in Crab Orchard Township. He is part of a family whose weddings and parties appear routinely in newspaper society pages, a family that has owned hundreds of Mecklenburg acres for a century, likely longer (take a look at that history here.)

- Emma Moseley, described by the Charlotte Observer as a “negro house girl,” is one of the witnesses who will say Grier’s niece pushes the gun away. (The Observer’s sub-headline: “Child Prevented Shooting.”) She will say the child is the daughter of a sister who’s been staying with Grier. Census records show two Grier sisters with young daughters at this time, one in a neighboring township, one living in Concord.

- Jonas Malcolm, another Black tenant, is the other witness saying the niece pushes away the gun. He will add that he speaks to McDaniel a few moments into his flight from Grier’s house. McDaniel’s lip is bleeding, and he tells Malcolm he fell and bit it while running.

- Black tenant farmer Fred Moseley will testify that Grier comes to his home and asks to search it for McDaniel, who is not there. (Grier will confirm this.) Moseley will say he asks Grier what the problem is and Grier replies: “You’ll find out.” Fred’s mother, Alice, will echo that in her testimony: When she asks Grier why he’s seeking McDaniel, he tells her: “If I find him, you’ll find out.”

- Grier will say he follows McDaniel 20 minutes after the confrontation – not in anger but because, as the Observer puts it, he “happened to remember” McDaniel hasn’t fed the mules, and pursues him, with a gun, to tell him to do so.

A Black man, unnamed, will later report he hears a shot this afternoon, in the woods below the McDaniel cabin.

About 3 p.m.

Grier travels about 8 miles into town, to the Mecklenburg Rural Police station, in the courthouse basement on East Trade Street, to tell Chief Vic Fesperman about the confrontation. (Read about how the Rural Police came to be, and what they became, here.)

Why would a farmer go the significant distance into town to do this? Stories don’t offer a clear answer. Fesperman says, according to an Observer story, that Grier wants to swear out a warrant against McDaniel – for what, it doesn’t say – but decides not to when Fesperman advises him “not to press the matter further.” But another story cites a Rural Police officer saying Grier had decided before arriving, on the advice of “a relative,” not to seek a warrant.

Then why would he have come? To tell Fesperman what had happened? To seek advice? To request other action?

Mell Grier and his older brother Joe Grier are quite familiar with county law enforcement: Joe (later known as Joseph W. Grier Sr.) married the daughter of longtime Mecklenburg Sheriff N.W. Wallace in 1914, with the Observer deeming the wedding “one of the leading social events of the fall.” Wallace’s son Jack lived with a Grier cousin for a time, and Mell’s farm borders sizeable chunks of Wallace family land.

Fesperman, Wallace’s deputy for a long stint (including in 1913, when Joe McNeely was lynched) has been a fixture in Mecklenburg law enforcement for 25 years. He’s been chief of Rural Police — a force separate from city police and the county sheriff — since the job was created in 1924. He was sworn in five months after his son John went on a “raid” with Rural Police officers and was killed by a Black man. That “raid” was later deemed illegitimate, in such serious ways that the governor commuted the Black man’s death sentence. (Read what the governor wrote about that “raid” and about its continuing presence in Charlotte here.)

By 1929, the Rural Police have grown to 13 officers, including another Fesperman son, and by tomorrow, Vic Fesperman will be in charge of the investigation of Willie McDaniel’s death.

Throughout that afternoon and evening.

Where is Willie McDaniel – or his body – during this time?

Jim Edmonds, who with his wife shares the McDaniels’ cabin, will testify he seeks and calls out to McDaniel all Saturday afternoon and into the evening, through fields and woods nearby.

He will say that in that time he twice passes the place where McDaniel’s body is eventually found, and nothing is there.

That evening.

Edmonds goes to Grier’s house, he will testify, and asks Grier to “patch things up and let Willie come back.” Edmonds quotes Grier’s reply, reports the Observer: “He’ll come back, all right.”

Grier goes to bed at 9:50, he will tell the coroner’s jury.

Edmonds will testify his dogs bark at about 11 p.m., and he goes to his cabin door, but doesn’t see or hear anyone. One of the dogs barks again a moment later, he will testify, at the barn, which is about 50 yards from where McDaniel’s body will be found tomorrow.

No one has seen Willie McDaniel, according to witness testimony, since a little after noon, when he spoke those few words to Jonas Malcolm, then continued to run.

Discovery, and ominous words

Sunday, June 30

About 6:30 a.m.

A young Black girl, unnamed in reports, finds McDaniel at the edge of a cotton patch and woods near his barn, and goes to tell Edmonds, believing McDaniel asleep. He tells her to go back and wake him, he will testify. She returns to say she can’t. Edmonds goes, and finds McDaniel dead.

Joe Grier, not Mell, telephones the Rural Police, Fesperman will tell the News. Black people had “sent word” to Mell Grier that they’d found the body, Fesperman will say, and the Grier brothers, “remembering the difficulty of the day before,” decide to call in the Rural Police. Fesperman will say the three of them go together down into the woods, to the body.

At this time, Joe Grier lives with his wife and teenage son on Queens Road West in Charlotte, some 10 miles from Mell Grier’s farm. No testimony is reported about when or how Joe has gotten to Mell’s land.

According to Fesperman, he and the Grier brothers find what the News calls “a large group of negroes surrounding the body.”

Descriptions by Black people of his body when found will surface in coming days.

Mell Grier’s testimony will disagree with Fesperman’s: He will say that after about noon on Saturday, when he watched McDaniel flee from him, he never saw him again, alive or dead.

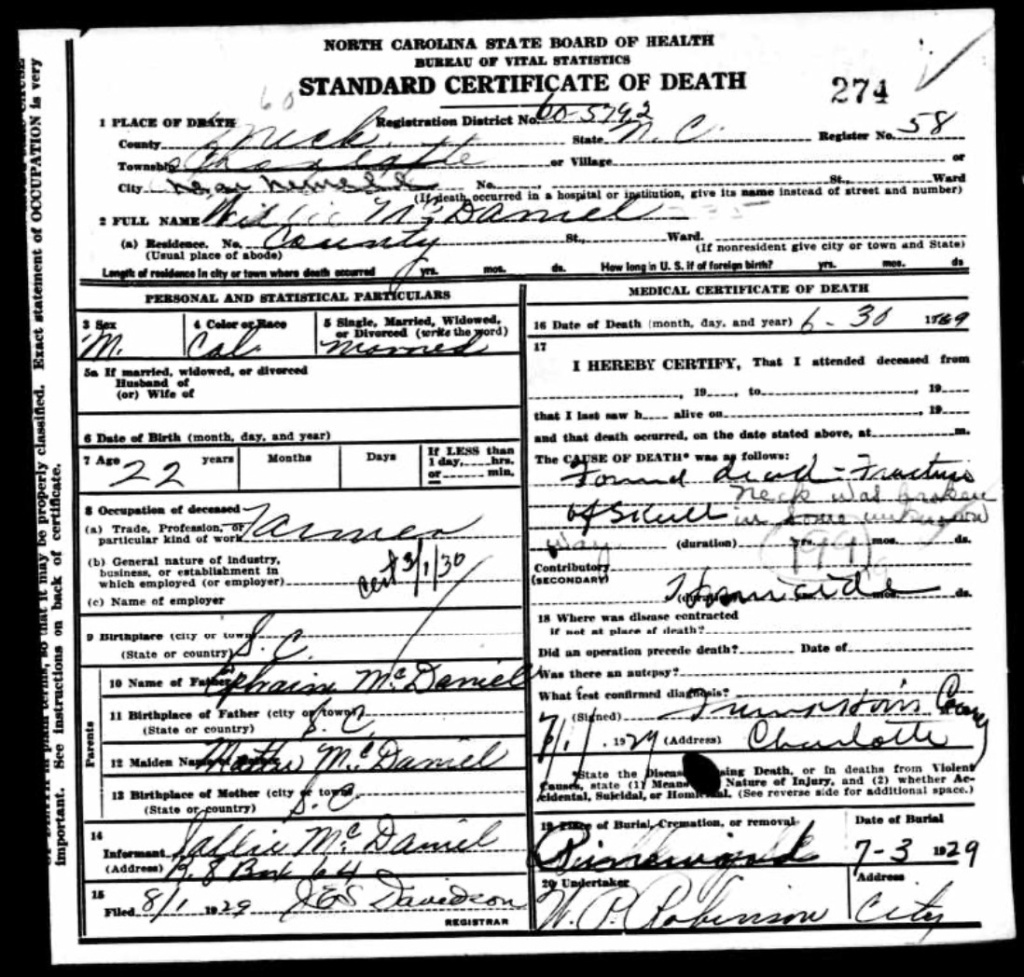

Doctors C.S. McLaughlin and L.B. Newell are called to examine McDaniel – but their findings will not be made public until two days from now, July 2.

Later Sunday.

Edmonds goes again to Mell Grier’s house to get “the straight” of what happened, he will testify, since Grier was the last person he saw with McDaniel and Grier was “following him with a gun.”

Grier, he will testify, says: “Uncle Jim, I didn’t do it. He brought it on himself.”

Edmonds will later say that this is the day he moves off the Grier property.

The investigation begins

Monday, July 1

This afternoon’s Charlotte News story, the first on the killing, says the cause of McDaniel’s death is a “secret closely guarded by officials.”

This afternoon’s Charlotte News story, the first on the killing, says the cause of McDaniel’s death is a “secret closely guarded by officials.”

Fesperman notes a bruise over McDaniel’s right eye “not sufficient to kill him,” says the paper, and other “minor bruises.”

But he refuses to disclose the results of the doctors’ examination.

1st public mention of lynching

Tuesday, July 2

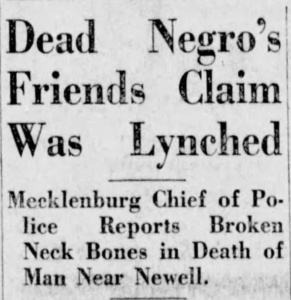

Well-known white Charlotte attorney Jake Newell announces that friends of McDaniel have hired him to investigate the death, and the Charlotte News headlines its story “Dead Negro’s Friends Claim Was Lynched.”

Well-known white Charlotte attorney Jake Newell announces that friends of McDaniel have hired him to investigate the death, and the Charlotte News headlines its story “Dead Negro’s Friends Claim Was Lynched.”

The story misspells Willie McDaniel’s name.

The people who hired this lawyer might have had their hopes for justice lifted by a significant court decision in March, in which an attorney’s defense convinced a Mecklenburg Superior Court jury not to sentence a Black man to death in the fatal shooting of a white police officer. (Read about that, and see how it was reported by a Black-run newspaper, here.)

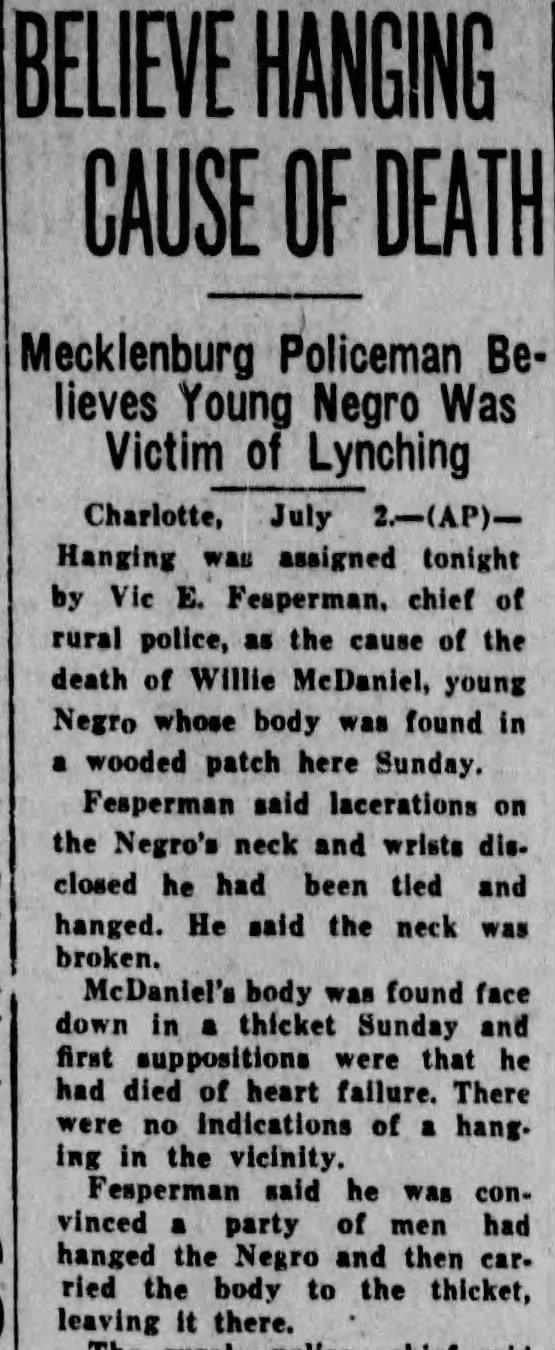

Raleigh’s News & Observer will run this story with the sub-headline “Mecklenburg Policeman Believes Young Negro Was Victim of Lynching.”

Papers from Georgia to Vermont will also publish this story.

But neither the Observer nor the News will include in their stories that Fesperman has suggested “a party of men” killed Willie McDaniel.

New clues, and a revelation

Wednesday, July 3

Attorney Newell and Charlotte Observer reporter LeGette Blythe both go to the Grier farm, talking with residents and examining the scene.

Blythe is one of few reporters to get bylines — his name on his stories — in the Observer. Less than a month ago, he covered the parade down Tryon Street for the 39th annual Confederate Veterans Reunion (take a look at photos here) — a multi-day event for which the Observer ran the front-page banner headline “CITY SURRENDERS TO CONFEDERATE ARMY.” The parade drew a crowd estimated at 150,000 by the Observer, what the News called “a howling, vociferous throng.” Blythe’s story described at length “the glory and the glamor of a nation founded in deathless principle”: the Confederacy.

Today, returning from the Grier farm, Blythe has a theory.

Blythe identifies a white oak 150-200 yards behind Grier’s barn and writes in his story for tomorrow’s Observer that “clues strongly indicat(e) that a lynching party took Willie McDaniel … hanged him and then dragged his body across a cotton field and left it face downward near the negro’s own barn.” This oak has a large limb horizontal to the trunk, about 15 feet off the ground, Blythe writes, and moss and bark appear to have been rubbed off its top, “as if by an encircling rope.” He notes tracks, and trampled brush, and a place halfway between the tree and where the body was found, where grass is flattened as if something had been laid down.

His theory begs questions: When could this have been done during the day, with Edmonds searching the property and other tenants around? If it was done after nightfall, where had McDaniel been all afternoon?

Blythe finishes his story on a chilling note.

The death has reminded neighbors here of another mysterious killing: A Black farm laborer found with a bullet wound in the back of his head “several years” before, “in the neighborhood of the place where McDaniel’s body was found.” The death, says a white resident, was never explained.

Who killed Craig Kirkpatrick?

A deep dive into Charlotte newspaper archives finds a plausible explanation for what the neighbors recalled. These two cases have not been examined together, at least publicly, before.

A deep dive into Charlotte newspaper archives finds a plausible explanation for what the neighbors recalled. These two cases have not been examined together, at least publicly, before.

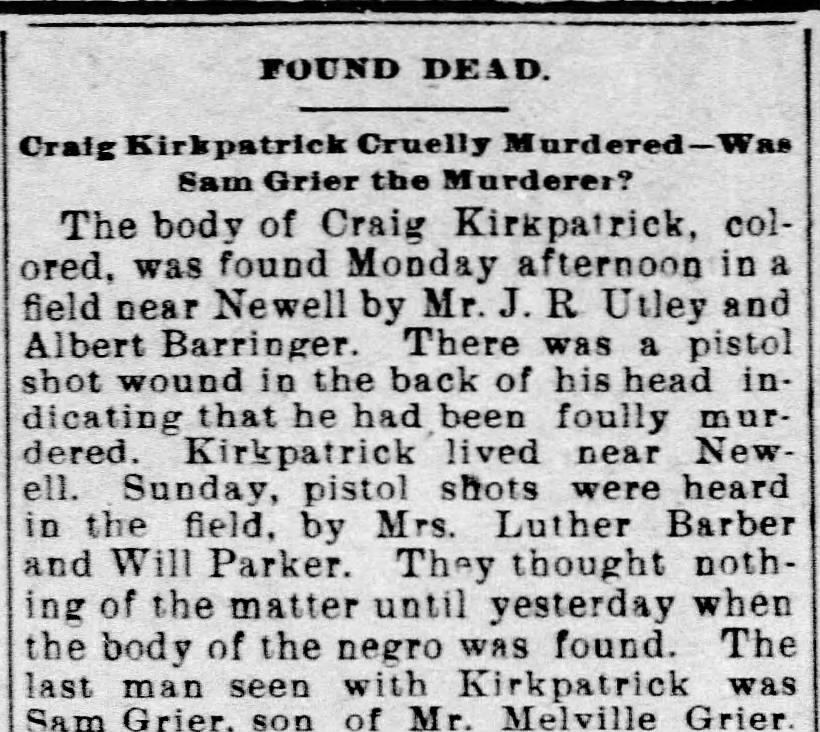

In March 1896, the Charlotte Democrat, the Mecklenburg Times and the Daily Charlotte Observer (March 4 edition shown) reported the death of Craig Kirkpatrick, saying the man last seen with him was Sam Grier, son of “Melville Grier.”

The Black man’s body was found, neck broken, in the woods between his home and that of Melville Grier, near Newell, in Crab Orchard Township – 33 years and 3 months before Willie McDaniel’s body was found, neck broken, on the edge of woods between his home and that of Mell Grier, near Newell, in Crab Orchard Township.

Melville Grier in 1896 is not the man renting farmland to Willie McDaniel in 1929. News stories of the time, census data and deeds indicate this was instead James Melville Grier, sometimes called Melville, whose son Sam was 23 in 1896. James Melville Grier was Mell Grier’s uncle (Sam his slightly older cousin) and deed records show James Melville owned land at this time adjoining what will be Mell’s land in 1929.

In the back of Kirkpatrick’s head was a bullet from a .38 pistol, which reportedly broke his neck.

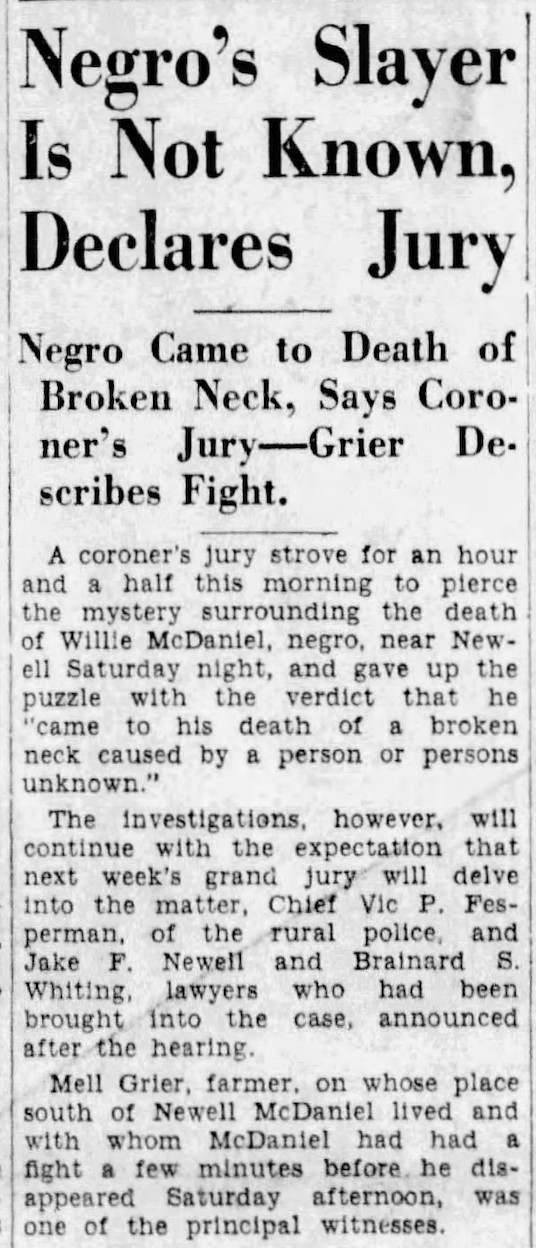

In four days, with no witnesses, a coroner’s jury ruled that Sam Grier alone committed the crime – and Sam, newspapers reported, “has disappeared.”

Someone had tried to burn Melville Grier’s barn, the Observer wrote, and “The supposition is” that Sam “believed Kirkpatrick was the guilty party, and that he settled accounts with him by putting the bullet into his neck.” But when the coroner’s jury looked into evidence, it decided “Kirkpatrick’s foot did not fit the track about the barn, and it is not thought that he set fire to it.”

A month later, a Mecklenburg grand jury indicted Sam Grier for murder. Papers in both Carolinas would repeatedly cite his alleged reason for killing Kirkpatrick, but mention nothing of Kirkpatrick’s announced innocence, as they continued to report Sam Grier was nowhere to be found.

And Sam Grier would never be brought to trial. Why? Read more here.

Offer of 'aid' and a new theory

Thursday, July 4

In Charlotte, Mell Grier’s brother Joe goes to Fesperman’s office to, as this afternoon’s News puts it, “offer such aid as he could in clearing up the mystery” of who has killed Willie McDaniel.

What aid that might be is not reported.

Fesperman says he still has no clues — though he told the News yesterday he was looking into “the tracks of two men” on the Grier farm — and police summon “10 or more” witnesses to testify before the coroner’s jury.

That evening.

The Rural Police share a new theory with the Observer: McDaniel was hanged in his own barn loft Saturday night, after being either carried from his home or caught nearby.

Fesperman dismisses Blythe’s theory, saying the tree behind Grier’s barn is too far from where the body was found — about 300 yards — for the 185-pound McDaniel to have been carried. The tenants’ own barn is just 50 yards from it.

But if Fesperman believes, as he said two days ago, that a “party of men” committed the crime, why would he suggest McDaniel’s body couldn’t have been carried this far?

One more “conjecture” from the Rural Police station: McDaniel “was killed by a rival group of negroes.” Others at the station scoff, however, the paper reports: “They had never heard of negroes carrying out a hanging.”

Quick verdict, then a stunning letter

Friday, July 5

11 a.m.

Six white men — Davis Robinson, Robert Watkins, A.L. Norman, Frank B. Phillips, Boyce Simpson and Bob Byrd (says the News) or Robert Boyd (Observer) — form the coroner’s jury that hears the case this morning.

Testifying are Grier; Fesperman; Drs. McLaughlin and Newell; Black residents of the Grier farm: Jim Edmonds, Sallie McDaniel, Jonas Malcolm, Fred, Alice (Fred’s mother) and Emma Moseley, George Hurd and his wife, Sarah; and other Black people not identified by name.

A juror asks Sallie McDaniel during her testimony where her husband is buried. That is how she discovers that he has, in fact, been buried — two days ago.

His family and friends had not been told.

The undertaker says he had not been paid and it didn’t appear he would be, so he buried McDaniel in a pauper’s grave — the term for where poor, unnamed or unclaimed bodies are buried — in a Charlotte cemetery identified as Piney Grove.

(This is actually Pinewood, on 6th Street, fenced off at the time from whites-only Elmwood. Pinewood is the burial place listed on McDaniel’s death certificate — and also that of Joe McNeely, lynched in Mecklenburg in 1913. The cemetery, still in existence, remained segregated until 1969. Its records show McNeely and McDaniel buried in “city ground” – designated for the poor and marked “Potter’s Field” in the map here – but give no specific location for either man’s grave. They have no markers.)

Asked a question by the coroner, Edmonds, who shared a cabin with the McDaniels, testifies that he too has had what the paper calls “some trouble” with Grier in the past, and that Grier has been “pretty hard to get along with.”

The doctors, McLaughlin and Newell (coroner Hovis is not a doctor), testify.

They note their examination showed a broken neck and injuries to neck and wrists, giving them “the impression,” the News says, he had been hanged.

McLaughlin also says McDaniel had a “slight cut” over one eye and “cuts” on his right arm and knee, according to the Observer. The News calls these “bruises.”

There is no reported testimony about any other injuries.

Yet in yesterday’s Observer, reporter Blythe wrote that McLaughlin’s examination “disclosed the fact that … [McDaniel] had been struck a heavy blow on the head. This blow, however, it was announced, was not sufficient to cause death.”

And this morning’s Observer reported that the doctors’ exam noted “a severe gash across his forehead, which was not serious enough, however, to cause death, according to Dr. McLaughlin.”

Has that gash now become a “slight cut”?

Testimony wraps up.

Reporter Blythe, who had been expected to testify, is not called.

Newell, who has been a Charlotte attorney for more than a decade, conducts no examinations of witnesses, notes the Observer, and tells the paper that “he was told it was not customary” for anyone except the coroner or jury members to ask anything.

Also noted by the Observer: Nothing in testimony shows “that any of the premises on the Grier farm had been searched for evidence.”

Robinson, Watkins, Norman, Phillips, Simpson and Boyd or Byrd deliberate for 90 minutes and declare they cannot solve the puzzle of who committed this crime.

Their verdict: Willie McDaniel “came to his death of a broken neck caused by a person or persons unknown.”

The “heavy blow,” the “severe gash” and the “fracture of skull,” listed on his death certificate next to “neck was broken,” are not mentioned.

A 'White Man' writes

After the hearing, Fesperman, attorney Newell and Brainard S. Whiting, who is helping Newell, announce they expect next week’s regularly scheduled grand jury to take up the case.

Then, says the News, Newell reveals a surprise:

He has received a letter — mailed in Concord, he specifies – signed “A White Man.” It gives the names of witnesses with information “which should explain some phases of the killing.”

“The writer,” the News goes on, “said that he would be willing to disclose his identity except that if he did so, it would mean his death. Mr. Newell said that he would investigate fully.”

This letter and its contents, including names of witnesses and its curious choice of the word “phases” — what could that mean? — do not appear again in any reports.

One newspaper labels it a lynching

The Friday Charlotte News’ editorial page, at the bottom of Page 8, names the crime a lynching.

“Apparently a negro has been lynched in Mecklenburg County and from what facts as are out in the open, it was about the most excuseless lynching that has ever occurred anywhere in any land.” It declares Mecklenburg residents are “a community of Church people and of the best type of citizens” but: “Even so, right among these an outrageous act has been committed.”

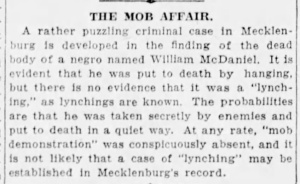

Tomorrow’s Observer will disagree: It will argue McDaniel’s death was not a lynching and doubts the county’s reputation will have to endure another stain:

Tomorrow’s Observer will disagree: It will argue McDaniel’s death was not a lynching and doubts the county’s reputation will have to endure another stain:

“ ‘(M)ob demonstration’ was conspicuously absent, and it is not likely that a case of ‘lynching’ may be established in Mecklenburg’s record.”

This calls to mind how the Observer had approached lynching 16 years before, first predicting Mecklenburg “never will have one,” then claiming the city had been “humiliated as never before” by the killing of Joe McNeely.

Gun as possibility?

Saturday, July 6

Willie McDaniel’s body will be exhumed and re-examined after a petition by his widow, it’s announced.

Attorney Newell says a Black woman told him yesterday she knows for a certainty McDaniel was shot and that one side of his body was bloody when discovered. He also says a Black man who lives in the area told him he didn’t know anything about the killing – “except I heard the shot,” near the McDaniel cabin.

Edmonds, who says he’s now abandoned his crop on the Grier farm and moved to Charlotte with his wife and Sallie McDaniel, also says he believes McDaniel was shot.

When he first found McDaniel’s body and turned it over, Edmonds says, he noticed “many small wounds from which water and blood were oozing,” on his face and “about the neck and shoulder,” the Observer reports.

It continues: “These wounds, he was convinced, were caused by shot from a shotgun.”

Edmonds says he did not tell this to the coroner’s jury because he was afraid. But he says he did tell the authorities on the day McDaniel’s body was found, the News reports, and pointed out the possibility that “a load of shot or a bullet had entered the throat leaving a mark which was taken for rope mark.”

Those authorities “overruled that idea when the doctors found that the neck had been broken,” reports the News.

Such an “overruling” would ignore two significant possibilities: One is that bullets or shot (pellets from a shotgun) can break bone (as a bullet was judged to have broken Craig Kirkpatrick’s neck nearby in 1896).

But another, clearer possibility is that McDaniel might have been shot and had his neck broken, in some other way.

This idea — that a broken neck might have caused his death, but he might also have been shot — will not be what’s emphasized by the Charlotte newspapers.

Tomorrow’s Observer will remind readers that McLaughlin and Newell found wounds in their first examination but said they “were entirely superficial and did not contribute to his death.” The story says the exhumation is largely happening because “several negroes” say they know McDaniel was shot – which would mean, it specifies, that he “came to his death from a gunshot wound instead of having been hanged.”

The News will say “insistent reports” have claimed McDaniel was “shot to death” and that Edmonds raised the idea that a load of shot broke McDaniel’s neck and that, if true, “therefore, he was not hanged.”

But the question is not necessarily either-or.

Looking in detail at how the injuries are described at different times is relevant to understanding what might have happened.

Could any of the smaller injuries noted in the original doctors’ examination — described variously as “cuts,” “bruises,” “scars,” “marks,” “abrasions,” “lacerations” and “slight wounds,” some on neck and wrists but some over an eye, on an arm, a knee, his forehead — align with what the unnamed Black woman and Edmonds are saying?

Is it possible any of those injuries were shallow shotgun pellet wounds – as Edmonds said he believed them to be?

That McDaniel was shot, just not fatally? That the breaking of his neck came separately?

What might that mean?

To answer this adequately, the exhumation must address whether any of those originally reported injuries could have come from McDaniel being shot — not just whether or not a shot broke his neck.

Coffin unearthed; questions unanswered

Sunday, July 7

10 a.m., one week since Willie McDaniel’s body was found.

Scores of people, Black and white, including Sallie McDaniel and fellow tenants on the Grier farm, gather to watch on this cloudy Sunday morning as Willie McDaniel’s body is exhumed at Pinewood Cemetery. Three feet of dirt are removed, and the coffin, a cheap wooden one the undertaker billed to the county when he buried McDaniel without telling his family, is pulled from the ground, then opened.

The crowd is shocked.

His body is unclothed, only a single piece of heavy brown wrapping paper around him, with excelsior — wood shavings, used to pack goods or stuff upholstery — packed into the coffin’s corners.

The Black people in the crowd, the Observer will report, are “especially horrified.” An older Black woman who identifies herself as a McDaniel cousin is visibly upset: She says she took a suit and other apparel to the undertaker’s, and was promised he would be buried in them.

The crowd watches as McDaniel’s body is laid onto the lid of the coffin to be examined. A new doctor to the case, William Wishart, steps up. The two who initially examined the body, Drs. McLaughlin and Newell, are also on hand, at attorney Newell’s request.

Wishart conducts his examination, “probing the wound” at McDaniel’s neck, the News will report, then says the neck abrasions are not deep, that they are not the result of being shot, and that his findings concur with the original post mortem – that the neck was broken in a way that suggests he was hanged. The News’ sub-headline will say “No Indication of Death by Shooting.”

The Observer’s headline will be “Broken Neck Caused Negro’s Death, Autopsy Reveals.” It adds a sub-headline “No Gun Shot Wounds Found on Body,” but also specifies that Wishart sees “only the wounds testified to” in the first doctors’ examination — testimony that included those minor, non-fatal wounds that “did not contribute to his death.”

Neither report will address whether or not any of his non-fatal wounds might be the result of being shot, nor will there be any mention in Charlotte papers of the fractured skull, the “heavy blow,” the “severe gash.”

Later in July, the Philadelphia Tribune, a Black-run newspaper, will run a story from the Associated Negro Press saying the exhumation did not show any “bullet wound,” but that it did confirm a broken neck —and “evidence that he had been severely beaten.” It will give no more details.

This day, with the exhumation finished, Willie McDaniel’s body is wrapped up — again, in only brown paper — and returned to the coffin. Excelsior goes back into its corners, its lid goes back on.

Sallie McDaniel says she had hoped to return her husband’s body to Richburg, S.C., near where his father and siblings still live, but she cannot afford to. Instead, she watches as he is buried for the second time.

She places wild daisies on her husband’s grave.

Today’s News reports new “speculation” that “a small mob” hanged McDaniel, and that an unidentified man on the coroner’s jury has floated the idea it was “some organized group.”

Mecklenburg's 'good name'

Monday, July 8

Solicitor John Carpenter (a solicitor is essentially a prosecutor) announces he will start an investigation and present facts to the Mecklenburg County grand jury – which begins its already-scheduled six-month term today, with a two-week criminal case session.

“It was a terrible thing and the people of Mecklenburg County have a right to have it cleared up,” the Observer quotes Carpenter as saying, making clear his priority: “The good name of the county demands it.”

One more piece of news emerges this day in the Observer: “One of the most prominent criminal lawyers of Charlotte,” not named, tells the paper that relatives of Mell Grier approached him last week. They discussed the case, the lawyer is quoted as saying, “just as citizens would naturally do in trying to help find out who the guilty parties are.”

The lawyer “did not say,” writes the reporter, whether the family has retained the lawyer’s services.

No further 'delusions'

Tuesday, July 9

“Let Us Have No Further Delusions,” says this afternoon’s News editorial page: “(T)here has been a lynching in Mecklenburg County. We have to accept that ugly fact….”

Then it continues: “Of course it was only a negro who was lynched. That, usually, is what is said when these situations abound, but what of that? If the law made it a felony to take a yellow dog out and hang him to a tree contrary to law, that would be a crime … (T)here are some who do know about this thing. We submit that it is the duty of the good people of the community in which the lynching occurred to be the first to move in the matter…”

Solicitor Carpenter says he plans to go to the scene of the crime this evening, and announces that a Black man has been arrested for something unrelated — “but we believe he knows something about it.” Carpenter suggests other people also will be arrested.

Arrests ... but not of suspects

Wednesday, July 10

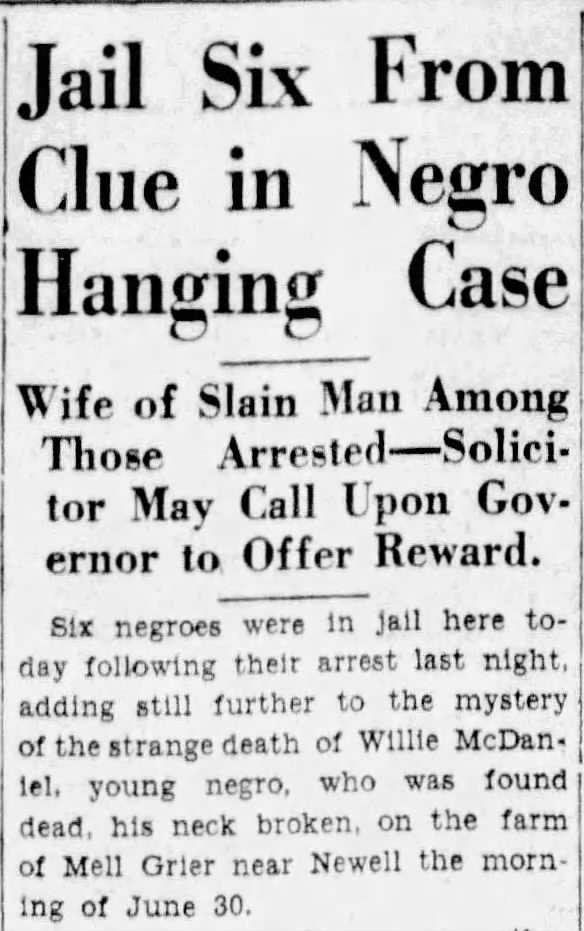

Police indeed make arrests — but not of any suspected killers of Willie McDaniel.

Police indeed make arrests — but not of any suspected killers of Willie McDaniel.

Instead, they announce they have arrested Sallie McDaniel and five other Black tenants: The News lists them as Fred Moseley; James Malcolm (identified elsewhere as Jonas); and George, Emma and Henry Hurd. (There’s likely a mistake here, as George’s wife has been listed elsewhere as Sarah, and an Emma Moseley has been named several times. But since only the News reports the names of those arrested, they can’t be cross-checked in the Observer.) All were arrested at the home of Jim Edmonds, where they had gathered the previous night. They are locked into separate cells as “material witnesses” for the grand jury.

Fesperman suggests, according to the News, “that sensational developments are expected” and that the arrests were the result of “a wholly unforeseen clue.”

Solicitor Carpenter is more specific, to the Observer: Sallie McDaniel has told him that on the night of June 29 (the date of the argument and chase), as she went to get water from a spring on Grier’s land, she saw a man flee through the woods.

She said that man left behind a green “hand stick” — likely meaning a cane.

These arrests follow multiple mentions in stories that the Black people living on the Grier farm “know something,” yet are “scared to death,” “terrified,” intimidated by “some influence which makes them fear for their own personal safety.” No conjecture on who, or what, is offered.

The Charlotte News this day says: “All the ear marks of a lynching bee were evident, except that no one, including the negroes who were on the place, would admit having seen or heard of a crowd.”

If the News suspects a lynching, is it difficult to imagine what’s causing the fear – or the simple refusal to speak?

That evening.

The Rural Police and Jake Newell say the hand stick may help solve the case, and that they believe it might have been used to twist a rope around, and break, Willie McDaniel’s neck.

Grand jury begins; Star of Zion questions

Thursday, July 11

The 18 white men of the current Mecklenburg grand jury session begin their investigation. Grand jury sessions are closed, so reporters list witnesses they are told appeared before the jury, but no actual testimony is reported, and no court records of it exist. The papers are told that several tenant farmers and Observer reporter Blythe testify this day.

Today’s edition of the Star of Zion, a Black-run weekly paper, has an editorial about the case, the only story in its available archives that refers to Willie McDaniel. (No archives are available of the city’s other Black-run paper, the weekly Charlotte Post, for this time.)

Its headline asks “Who Killed Willie McDaniel?”

The editorial notes that his body was found on Mell Grier’s farm and that “it is said McDaniel had an altercation with the farmer … and was seen running from the direction of his boss in apparent great fright.”

It asks: “Let us reverse this case. Suppose the shoe had been on the other foot? Would Willie McDaniel be at liberty?”

It concludes: “Who killed Willie McDaniel? Somebody knows, and the authorities should find them, and remove this disgrace from the State of North Carolina and the County of Mecklenburg.”

'Popularly accepted view': An enraged mob

Friday, July 12

The grand jury questions Sallie McDaniel for more than an hour, then says it plans to go to the Grier farm July 13. The News writes that the investigation is “surrounded with more secrecy” now than before.

The grand jury questions Sallie McDaniel for more than an hour, then says it plans to go to the Grier farm July 13. The News writes that the investigation is “surrounded with more secrecy” now than before.

Chief Fesperman says he is investigating two possibilities: The first is what the News now calls “the popularly accepted view that McDaniel was lynched by a small mob enraged at his having attacked Mell Grier” – which has not been reported in these terms before.

If that’s correct, who could have found out about the argument and pulled together a “mob” so quickly?

The second theory: McDaniel might have been “having trouble with his negro neighbors.” Fesperman is apparently suggesting Black neighbors might have lynched him, an idea Rural Police seemed to discard a week ago.

A disappearing hand stick

Saturday, July 13

Fesperman walks into the grand jury room carrying the green hand stick.

This is the item – dropped by “somebody I didn’t know,” Sallie McDaniel has said – that both the Rural Police and Newell heralded as the possible solution to the whole case, just three days ago.

The Observer reports that anything he revealed about it to the grand jury “could not be ascertained.”

The green hand stick is never mentioned again.

About noon.

Grand jury members adjourn for the day with no further information on the McDaniel case, but say they’ll go to the Grier farm Monday. They delayed, they say, “to give the group a longer time for inspection of the scene of the slaying.”

Jury says it's baffled about motive

Monday-Wednesday, July 15-17

After going to the Grier farm Monday, saying they hope to uncover new information — though what they think they’ll find two weeks after the body was found is not addressed — jurors return to the courthouse Tuesday and have Grier before them for the first time.

Grand jury finds nothing, is satisfied

Thursday, July 18

The grand jury, adjourning a two-week session, says it has failed to find any solution to the case, and will take it up again next session, in the hope “later evidence” will turn up.

Jurors say they were disappointed not to solve — or even find a clue to — the McDaniel case, but tomorrow’s Observer story will say they “admitted their satisfaction in knowing that they had done everything in their power to clear up the mysterious killing.”

The reportedly satisfied men on that jury are Price, H.B. Benoit, P.L. Bundy, W.R. Cornell, P.F. Davis, M.F. Ellis, W.E. Grier (who does not appear, in available genealogical or newspaper records, to be related to Mell Grier), G.W. Gurley, A.G. Hemby, J.F. Holbrook, G.M. Ketchie, George D. Kilgore, S.W. Maxwell, George H. Moore, S.C. Nixon, H.H. Tarleton, S.R. Wilson and M.W. Woodside.

Judge Thomas J. Shaw from Greensboro presided. Shaw also presided over the grand jury investigation of the lynching of Joe McNeely in 1913 — an investigation that also produced nothing.

The grand jury does recommend that a $250 reward be offered. Weeks pass. On Aug. 2, the county attorney announces that the county doesn’t have the legal authority to offer one, and the state won’t until the county does. A reward is never offered.

Another chance — then one more

Monday, Sept. 30 — Thursday, Nov. 14

Three months since Willie McDaniel’s body was found.

The Mecklenburg grand jury reconvenes Sept. 30 and adjourns Oct. 4 after a five-day session, with no indication of reopening the McDaniel case. Its eventual report on this session will not mention Willie McDaniel at all.

Six weeks later, on Nov. 14, foreman Price says the grand jury will take up the McDaniel case on Nov. 15, the last day before jurors’ terms of office expire — but he does not know whether any new evidence has been discovered.

The News’ story ends with this about McDaniel: “Whether he was taken by a mob was a question which engaged the public for weeks.”

The Observer story misspells Willie McDaniel’s name.

Grand jury adjourns, is praised

Friday, Nov. 15

Four and a half months since Willie McDaniel’s body was found.

The grand jury does not reopen the case, and adjourns for the last time in these jurors’ six-month term.

Tomorrow’s Observer will explain that what it now calls the “alleged lynching case” could not be reopened because “one witness was near death and the others moved to South Carolina.”

These witnesses are not named. The grand jury had heard from “more than 25” in July, according to the News, but no list of them, or who would have been called in a reopened case, exists.

Of the people reported as testifying in July — Mell Grier, Vic Fesperman, reporter LeGette Blythe — as well as the doctors, who likely would have been called — records show all will remain in Charlotte for years.

Of the six Black tenants who were jailed as grand jury witnesses — some of the people newspapers repeatedly described as fearful, intimidated by “some influence which makes them fear for their own personal safety” — none appear in the 1930 Census, in either of the Carolinas, under the names as reported in the papers.

The next grand jury will not pick up the McDaniel case.

Two days from now, an Observer editorial will congratulate the grand jury for the “effective and apparently conscientious work” it has done “to clear up various crimes, such as the Willie McDaniel homicide.”

In 1929, Iredell County native and son of formerly enslaved people Monroe Work, for Tuskegee Institute, will document seven lynchings of Black people – with apparently not a single prosecution – in the United States. Willie McDaniel’s death will not be included in his total.

In 1930, Monroe Work will document 20.

Friday, Oct. 5, 2018

89 years and three months since Willie McDaniel’s body was found

Willie McDaniel’s story does not come up again in a Charlotte daily newspaper until this day, in an article about the beginning of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Remembrance Project.

The Observer will not, in available archives of news and opinion pages, call Willie McDaniel’s death a lynching until this 2018 story. (It once attributed the word to Fesperman in a sub-headline, and put quotemarks around it to introduce Blythe’s story about the crime scene, in which the reporter says clues suggest a lynching party hanged McDaniel.)

But in all other cases, the Observer will choose other words: Murder. Slaying. Hanging. Homicide. Mystery.

No suspect has ever been named in Willie McDaniel’s murder. And — as is true of more than 99 percent of racial terror lynchings after 1900, according to the Equal Justice Initiative’s Lynching in America report – no one has ever been convicted of any criminal offense.

The Remembrance Project is working with Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation to schedule a soil collection and the installation of a historic marker memorializing Willie McDaniel at Reedy Creek Park and Nature Preserve. Get updates by signing up at the “Stay Connected” box at the bottom of this page.

If you read this without going to the additional linked stories for more background — on policing, court decisions, the Confederate parade down Tryon Street in 1929, and more — you can find those here: records used for this story; Willie McDaniel’s family; Mell Grier’s family; the Rural Police; an illegitimate police “raid” and the Alex Rodman story; the Clyde Fowler story; the 1929 Confederate Reunion in Charlotte; and more of the Sam Grier story.

Read Joe McNeely’s story here.

Read for yourself

Want to look at entire newspaper stories and/or genealogical records?

If you have a Charlotte-Mecklenburg library card, you can look at stories from the Charlotte Observer — the News is not archived there — by going to the Charlotte Mecklenburg Public Library’s Research and Learn site, then to Charlotte Observer, then searching. You might use names or specific words, and try limiting searches to a particular time period.

Newspapers.com has the Charlotte News and other papers, but it’s a paid service; it may offer a free trial.

If you’re interested in genealogy or want help researching your own family history, the library has a genealogy librarian: Danielle Pritchett is available via email at apritchett@cmlibrary.org or through the Carolina Room at carolinaroom@cmlibrary.org. She has also conducted classes at library branch locations.

Helen Schwab is a freelance journalist who was a Charlotte Observer editor and writer for 30+ years, and a consultant who has worked with public schools, artists and nonprofits.

This story is drawn from newspaper archives and a range of genealogical documents; the wide-ranging and ongoing work of historians Dr. Willie Griffin, J. Michael Moore, Dr. Pamela Grundy and Dr. Tom Hanchett; additional research by Brittany Foster and Deborah Whitfield of the Mecklenburg County Clerk of Superior Court’s office, Ida Harlson of the city’s cemeteries administration office, and Gary Schwab; and research assistance from Shelia Bumgarner, Tom Cole and Meghan Bowden of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Public Library; Lauren McCoy of the State Archives of North Carolina; and Philip McDaniel of UNC Chapel Hill; editing assistance from Harry Pickett.