This project began with bus trips to a memorial that offered horror — and a challenge.

By MAE ISRAEL

Say their names.

“Henry Smith, 17, was lynched in Paris, Texas, in 1893 before a mob of 10,000 people.”

“Mary Turner was lynched, with her unborn child, at Folsom Bridge at the Brooks-Lowndes County in Georgia in 1918 for complaining about the recent lynching of her husband, Hayes Turner.”

“Reverend T.A. Allen was lynched in Hernando, Mississippi, in 1935 for organizing local sharecroppers.”

As I walked in 2019 through the solemn corridors of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, I had to do it. Say the names of some of the thousands of African Americans identified as lynching victims in towns and cities across the country.

Tears filled my eyes as I looked up at the hanging, coffin-like, steel rectangles etched with their names and the dates they were killed. But it was a wall of death stories, revealing the senseless and heartless reasons that some people were killed, that pierced my heart.

I was strengthened, however, by being able to acknowledge these men, women and children in an extraordinary memorial honoring their lives, and revealing the scope and cruelty of racial terrorism.

A year later, I felt the same profound sense of loss. This time it was not rooted in past history.

I was shaken as I watched Minnesota police officer Derek Chauvin, captured on video, nonchalantly press his knee to the neck of a handcuffed Black man for more than nine minutes. George Floyd was killed. He was accused of using a counterfeit $20 bill at a convenience store to buy a pack of cigarettes.

I am still saying his name.

Joe McNeely. Willie McDaniel. Those are two more names I say now.

How the CMRP began

The bus trip that took me and other Charlotte-area residents to Montgomery helped lead to an ambitious initiative to memorialize McNeely and McDaniel, who died in lynchings documented by the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), which developed the Montgomery memorial.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Remembrance Project hopes to lift up the names of McNeely and McDaniel throughout the community, to spotlight what happened to them — in conversations, through storytelling, with markers and, eventually, by bringing a duplicate of Mecklenburg County’s monument from Montgomery back to Charlotte — and to help residents face, together, the impact of racial terror lynchings on all of us.

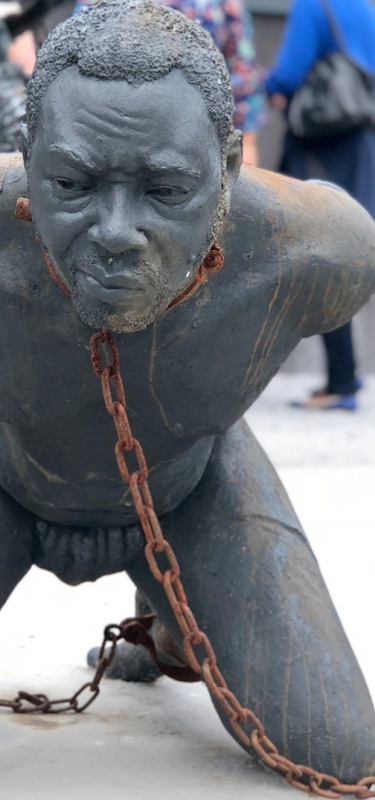

Six-foot steel monuments, more than 800 of them, fill the Montgomery memorial, one for each county in the United States where lynchings occurred. The monuments are engraved with thousands of racial terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950 identified by EJI. Thousands more lynchings occurred but cannot be documented.

Just as I did, Isaac Naylor traveled to Montgomery on organized bus trips, and went two times while a senior at East Mecklenburg High School.

He’s a history buff, and was eager to have a chance get up close to the history of lynching. A grandmother, he said, knows stories about lynching victims in her hometown, Little Rock, Arkansas, but doesn’t talk about it.

“When you walk below the metal squares suspended from the ceiling, it was like Black bodies dangling from a tree,” said Naylor. “That museum really changed the way I think about American history. Instead of reading about it, I saw the scope of how many people were killed. Lynchings were a spectacle.”

When he left the outdoor memorial, he said, “A lot of emotion flooded through me. I just broke down when I got on the bus. I was just kind of depressed for a little bit.”

Other students in the group cried too.

“I was talking to somebody about how we have modern-day lynchings that are filmed and videotaped,” Naylor said. “You could consider some police killings as racial terrorism. Unarmed Black people getting killed has been a common theme in American history.”

A friend comforted him, saying that “it is up to us” to continue fighting for fair treatment in our country’s justice system. “I found some solace in what she said.”

Charlotte’s bus trips began just months after the memorial’s opening, organized by groups including the Arts & Science Council, the Levine Museum of the New South, the Lee Institute, the Charlotte Teachers Institute and Race Matters for Juvenile Justice. In part, the collaboration and discussions among bus trip organizers and participants — teachers and clergy, business leaders and neighborhood activists, high school students and artists — helped form the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Remembrance Project.

“My hope is that people will know the stories, know the names of Joseph McNeely and Willie McDaniel,” said Kate Flynn, a former director with the Lee Institute who helped organize bus trips and is involved in the project.

“They will know it happened here. We need to talk about it. If we don’t, we won’t get to where we need to go in terms of equity.”

As for her journey to the memorial: “There is nothing that can prepare you for the experience.”

For many who traveled to Montgomery, visiting the memorial stirred more than deep emotion and reflection. Some say it has influenced their attitudes about social justice.

For most, it remains a tender and precious memory.

'What were they supposed to have done?'

“It was really overwhelming, honestly,” said retired Superior Court Judge Yvonne Mims-Evans. “Just to see the names. In some counties there were multiple people (lynched) on the same day. It was really a sobering experience.

“I still think about it. There was one of those monuments from a North Carolina county in the eastern part of the state with the names of two women with the same last name on it. I remember thinking, ‘What were they supposed to have done?’ ”

Mims-Evans, who went in 2018 as a representative of Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, was a member of the church’s Social Justice Ministry.

As she walked through the memorial, Mims-Evans said, she couldn’t help but think about the continuing violence against Black people.

“You keep thinking: When it is going to be enough to make a difference?”

Yvonne McCracken was so touched by her experience at the memorial in 2019 that she planned to return with her husband, Richard, and friends.

“I don’t think it is something that you can take in during one visit,” she said. “It needs repetition.”

Learning to look at history differently

The expanse of the lynching memorial, McCracken said, was overpowering.

“I was struck by the number of people it represents. I keep seeing that in my mind. It was such a waste of human life. I don’t see how you can look at it and not be struck by the enormity of it all.”

As a result, she now looks at history differently, said McCracken. “Sitting at dinner (during the trip), somebody said this isn’t about Black history but American history. That really hit me. That struck me as so simple and so true. It has made me want to read more, learn more.”

The Remembrance Project offers the specific stories of McNeely and McDaniel, told in a variety of formats, and supports community conversations designed to engage Charlotte residents in learning about this history. It also hosts a student essay contest, with monetary prizes.

'This history is still with us'

Alvin Jacobs is an image activist, spending his time capturing the power of people and places through photography. He deeply felt the artistry and symbolism in the memorial’s design, its surrounding sculptures and in its forceful messages.

“Some people want us to forget that this is how we were treated,” he said. “We are continuously told to get over it. It needs to never be forgotten. How many World War II memorials are there? How many Holocaust memorials are there? These are places of reflection and history. This is a history we have to maintain. If we don’t, we run the risk of revisionist history covering it up like it never happened. That does us all a disservice.”

Going to the lynching memorial was even more poignant than John Cox, director of the Center for Holocaust, Genocide & Human Rights Studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, had anticipated.

“The experience was substantially more overwhelming, intellectually and emotionally, than I could have imagined — and that is despite the fact that I had a good idea of what to expect,” said Cox.

He uses some of the information revealed at the lynching memorial in his classes and shares his experiences with his students as well.

“This memorial makes things a lot more human and impossible to ignore,” he said. “If anyone goes there, they will learn very clearly and persuasively that this history is still with us.”

Visiting the memorial led Elisa Chinn-Gary to think deeply about her father’s life. He grew up in Edgefield County, S.C., where several people were lynched during his youth, she said. Her visits to the memorial helped her imagine “what it must be like to encounter that level of violence and terror frequently.”

Chinn-Gary has served as Mecklenburg County’s Clerk of Superior Court and co-founder and co-chair of Race Matters for Juvenile Justice, which works to reduce the disproportionate impact of the justice system on young people and families of color. She’s also on the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Community Remembrance Project’s steering committee.

“In this nation, we hide things that are ugly,” she said. “We use soft language that tends to be inaccurate in giving the full story. I have challenged myself and those around me to be bold truth tellers.”

She recalls putting her hand on the Mecklenburg County monument in Montgomery, and taking a photo of it.

“I remember thinking to myself: ‘We are going to bring you home.’ ”

Mae Israel is an independent communications specialist, a UNC Chapel Hill journalism graduate who spent nearly two decades as an editor at the Washington Post and both reported and edited for the Charlotte Observer.