‘Never had a lynching ... never will’

Newspapers said Charlotte was different. Then a mob came for Joe McNeely.

By GARY SCHWAB

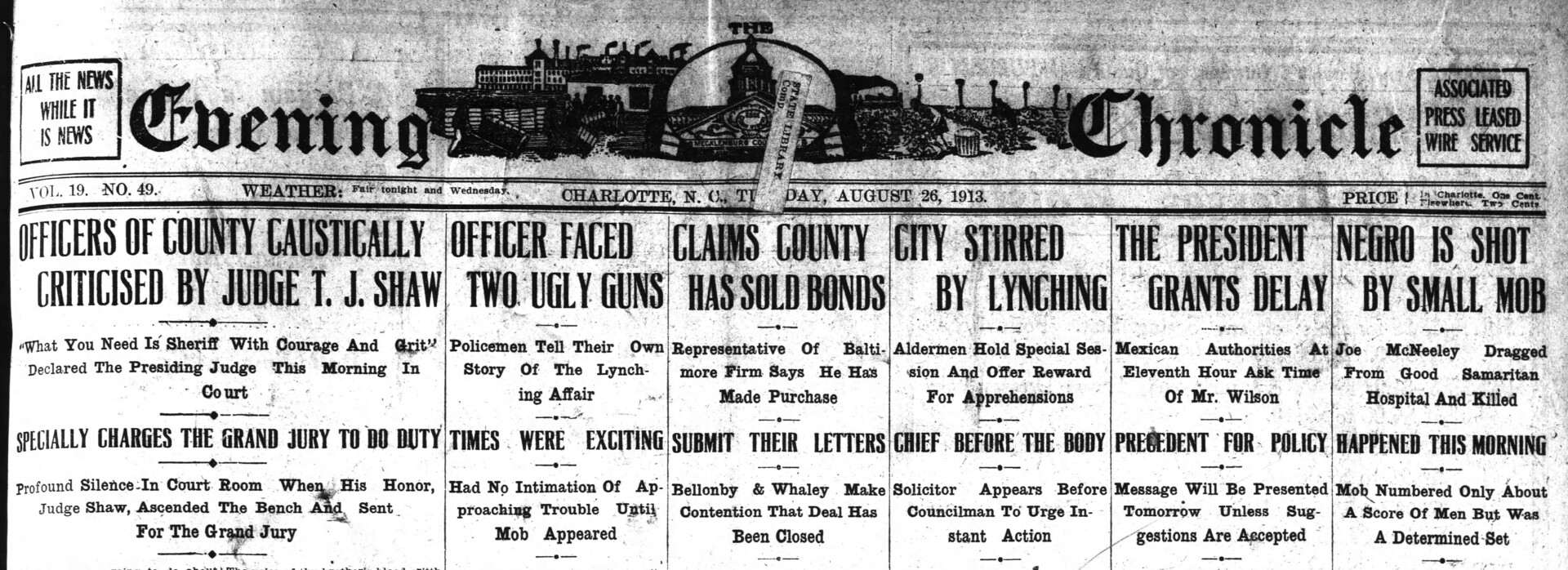

In August of 1913, Charlotte daily newspapers wrote that the city had never had a lynching and never would — just days before a mob of white men pulled Joe McNeely from his Good Samaritan Hospital bed, dragged him into the street in the dark of night and shot him to death.

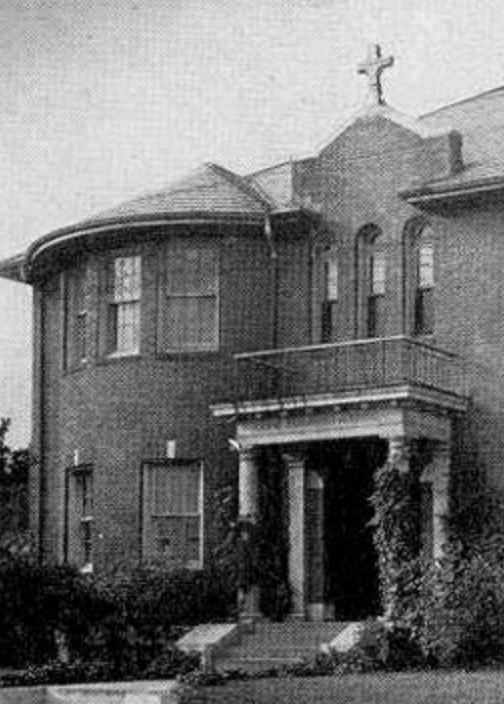

McNeely, a 22-year-old Black man, and white police officer L.L. Wilson had been in a confrontation on Aug. 22, leaving both men hospitalized with gunshot wounds: Wilson at whites-only Presbyterian and McNeely, in leg irons, on the second floor of Good Samaritan, Charlotte’s Black hospital.

Days later, at about 2:15 a.m.,Tuesday, Aug. 26, the mob arrived. Two police officers assigned to stand guard offered no resistance.

The Equal Justice Initiative has documented nearly 6,500 racial terror lynchings from 1865 to 1950, including a second Mecklenburg County lynching — of Willie McDaniel in 1929. Many more lynchings were never recorded.

Though lynching is most often thought of as hanging, other forms of fatal violence were also used, from shooting to burning to beating and more.

The spot where the mob lynched McNeely eventually became part of Bank of America Stadium, home of the NFL’s Carolina Panthers and the MLS’s Charlotte FC.

This narrative, the most detailed ever published, is a timeline of the 85 hours leading up to Charlotte’s first documented lynching and what followed, based on maps, census records and stories from the city’s three daily newspapers. It raises questions about what police knew, about what newspapers reported – and what they didn’t report.

Friday, August 22

A confrontation, then headlines of cocaine and impending death

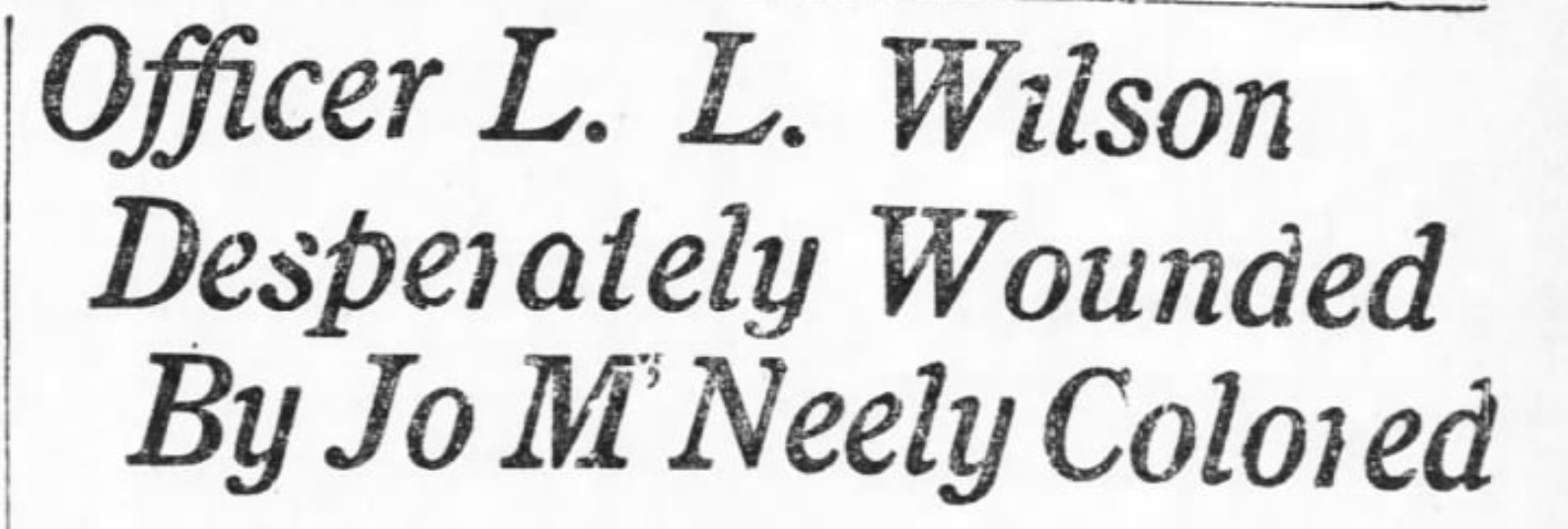

The Charlotte News and the Evening Chronicle both run front-page stories this afternoon, saying that a police officer shot earlier today will likely die.

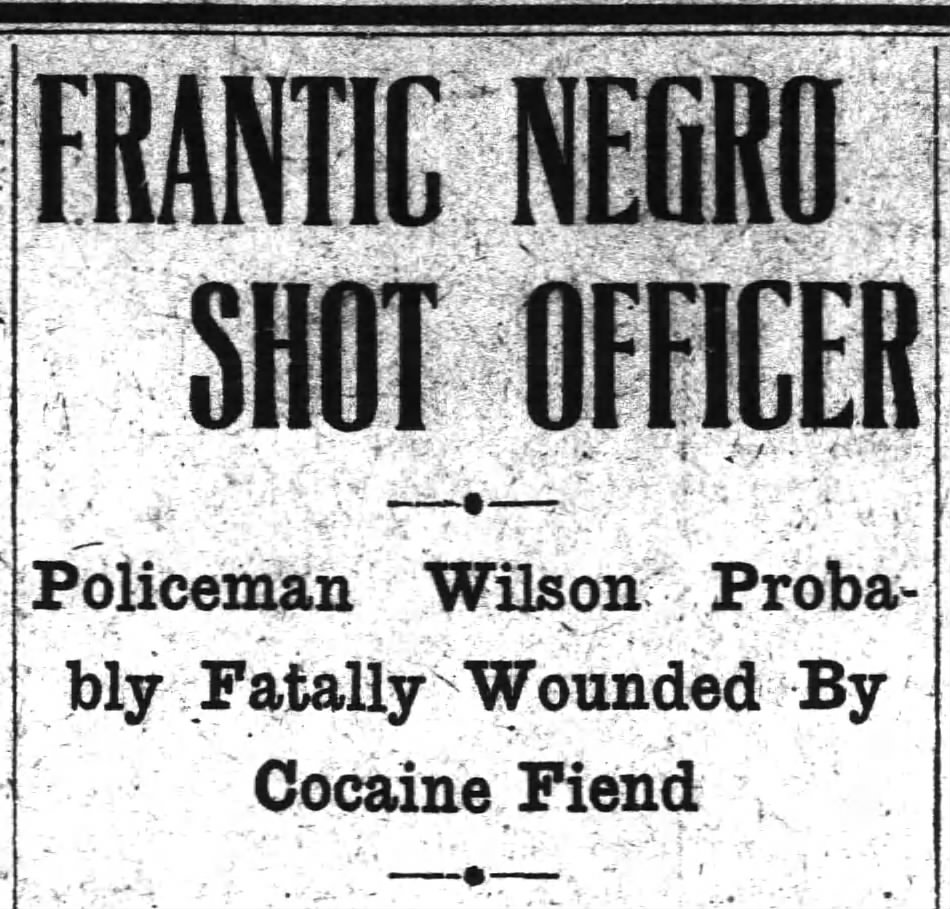

“Frantic Negro Shot Officer / Policeman Wilson Probably Fatally Wounded By Cocaine Fiend” is the Evening Chronicle’s headline.

From the first reports — some printed just hours after the confrontation between Joe McNeely and police officer L.L. Wilson on South Tryon Street — all three daily papers publish stories that appear mostly based on what police or unnamed bystanders say.

Rumors become headlines.

Stories say police received calls around 12:15 p.m. that “a negro man” (the papers don’t capitalize that word) had been brandishing a pistol and “shooting at everyone in sight” – though no one was reported hit or injured.

Police Chief Horace Moore sent Wilson to the scene, reportedly saying, “It might be a good chance for you to use that new gun that you have been showing around here.”

Wilson will later say that Moore ordered him to “go out and arrest a cocaine-crazed negro” – though there is no way Moore could have known whether McNeely had used cocaine. Police and all three daily newspapers say that McNeely is under the influence of cocaine, though no evidence or attribution is ever reported.

Within minutes, Wilson arrived on a motorcycle and allegedly was shot at close range by McNeely. Knocked off his vehicle, Wilson allegedly shot back, striking McNeely and then clubbing him with a blackjack.

The Charlotte Daily Observer (the word Daily will be dropped in 1916) on Saturday says surgeons believe “chances were greatly against Wilson.”

For days, speculation continues that Wilson likely will die — though he recovers – and that McNeely likely will live.

That speculation, newspapers will say, is thought to have triggered the mob.

Joe McNeely’s mother says her son is ill

Charlotte’s three daily papers – the Observer, the News and the Evening Chronicle – are owned and edited by white people, and their stories are written from a white perspective, though about one in three people in Mecklenburg County is Black. Available archives of the Black-owned Star of Zion don’t mention McNeely, though that paper is occasionally quoted by the dailies.

In a rare instance of a Black person being interviewed, the News quotes McNeely’s mother, after the confrontation, saying her son has been ill with fever for two weeks. It’s unclear what the illness is. Typhoid fever is in Charlotte at the time and can cause delirium. She says he left the house only when she went next door to see a neighbor, and when she discovered him gone, she sent another son to bring him back.

The News story doesn’t name his mother, but records indicate she is Fannie McNeely, who has lived with her husband, John, on South Tryon Street between Bland Street and Park Avenue, for more than a decade. Fannie and John had moved from Union County, where the 1880 Census lists John as a field laborer and Fannie as keeping house. In Charlotte, she has worked for years as a laundress; he has held various jobs. In years to come, he’ll work at the Chero-Cola Bottling Company on South Tryon, among other places, and their son Robert will work at an eating house on nearby Middle Street.

Saturday and Sunday, August 23-24

Weekend papers: 'The races live together in peace’

In 1913, Black people in America are regularly targeted by white mobs at even the suggestion of violence against a white person. Alleged offenses often are the catalyst for racial terror lynchings, especially if the situation involves white police officers.

But local newspapers say Charlotte is different, that Joe McNeely is in no danger at Good Samaritan Hospital, where he’s guarded by two police officers.

Sunday’s Observer says that Mecklenburg County “has never had a lynching in its history and it never will have one.”

The News says: “If a cocaine-crazed negro had ruthlessly shot an officer and attempted to kill other persons in many communities, serious race trouble would undoubtedly have followed…. In Charlotte, however, the races live together in peace.”

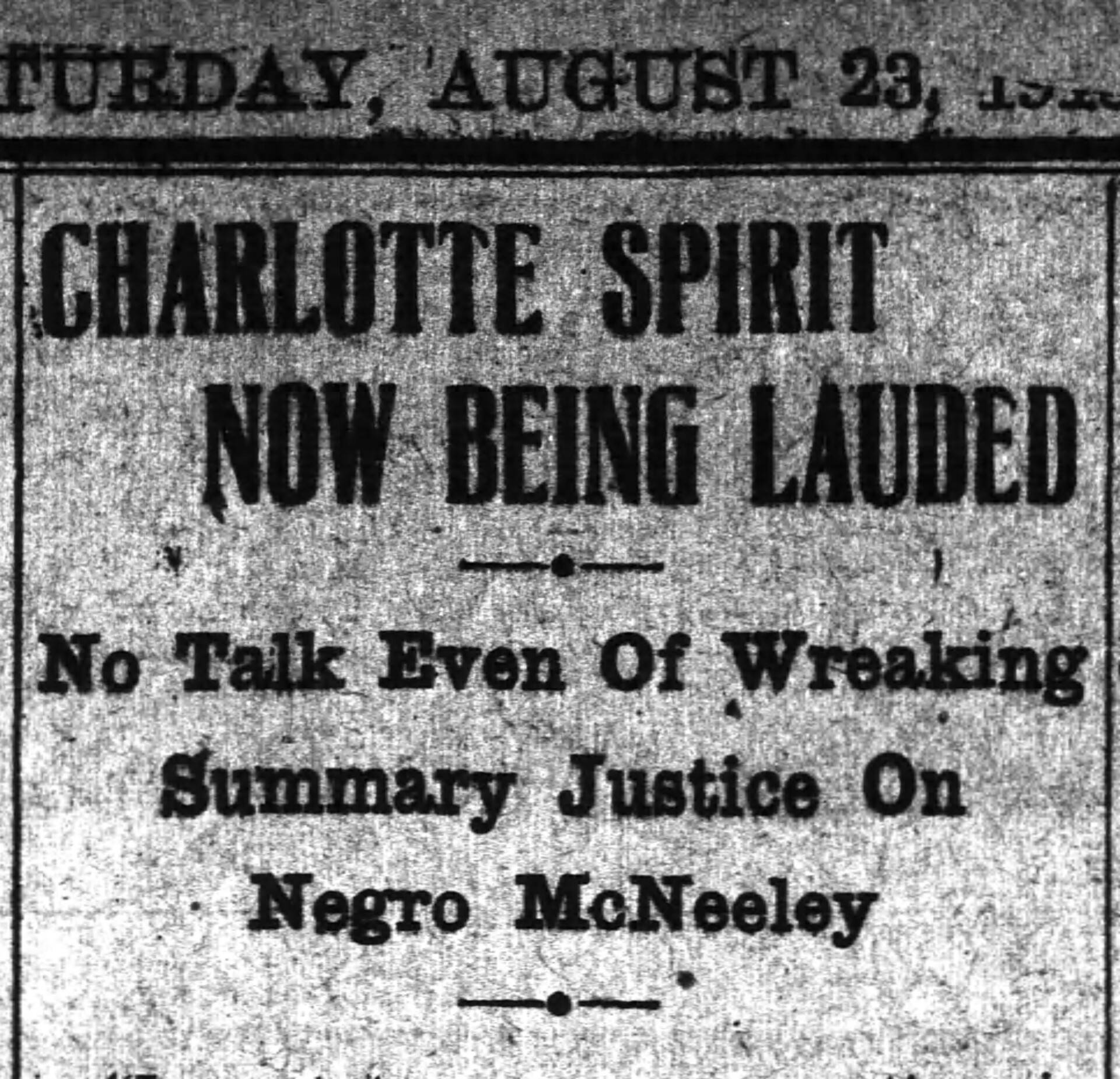

A Chronicle story with the headline “Charlotte Spirit Now Being Lauded” quotes an unnamed “prominent city official” talking about “the unusual spirit which has characterized Charlotte’s attitude toward” McNeely. It notes that police did not turn “Good Samaritan Hospital into an arsenal with the prospect of repelling an armed mob … recognizing that there was no danger to the negro from Charlotte citizens.”

Newspapers note there has not been a reported lynching in North Carolina for seven years.

It’s also reported that McNeely will be moved to the jail shortly.

Monday, August 25

Newspapers: McNeely has been 'very impudent' to police officers

The Observer and the Chronicle introduce a new inflammatory report Monday. Both papers, using the same phrase without attribution, say that McNeely is “very impudent” to police officers.

The Observer writes: McNeely has been “very impudent to the officers who have been on guard, so much so in fact that they have asked Chief Moore to move him to jail as soon as possible. When he came from the anesthetic and saw Mr. Pressley guarding him, he ordered the officer in rough language to get something for him, using oaths as he gave the order. Needless to state, the order was not carried out.”

McNeely’s tendency to insult the guards, the Chronicle will write after the lynching, “had much to do with inflaming the minds of certain people of the city who were aggrieved at the condition of Officer Wilson and might, after all, have been the real cause for the unfortunate occurrence.”

Also on Monday, the Chronicle praises Charlotte and presumes McNeely’s guilt: “It is a great commentary on the character of the city’s citizenship that there was not even a whisper against the life of the negro, who so completely deserved extreme penalty.”

The paper says McNeely was “rendered savage by cocaine.”

Should Wilson live, McNeely will be tried for assault with a deadly weapon – the penalty ranging from a few months to 10 years.

Hospital denies Observer report

The Observer continues to say Wilson likely won’t live. Its Monday headline says “Wilson’s Recovery Very Doubtful” and also says he shows symptoms of peritonitis (an infection that can become life-threatening), based on “several people who would know.” But that report is denied by the hospital, in the same story.

The newspaper says his hopes for life are “becoming weaker each hour…” The paper also says McNeely has no recollection of Friday’s shootings “or pretends that he has not.”

Word on the street: Something’s planned

Newspapers will say there was talk on the street of violence Monday evening but will never say who was talking.

Just before midnight, “it was whispered about the streets … that something unusual had been planned but nobody knew exactly what it was to be and most of those who heard the rumors believed that nothing would materialize, that too large a percentage would recede from their intentions when the critical moment came,” the Observer will report. It will note that no one took the rumors seriously enough to “take the steps which are ordinarily taken, such as calling out the militia or placing squadrons of police.”

Midnight nears; Tuesday, August 26, begins

Sheriff gets calls, yet says he had no warnings

Sheriff N.W. Wallace will later say that he had no warnings in time to prevent an attack nor did he “hear of any likelihood of any trouble of this character.”

But he gets three phone calls warning of trouble in the hours before the lynching, the News reports. There’s no evidence that he alerts Police Chief Moore, whose department has custody of McNeely.

The timeline, as reported by the papers:

- At 12:30 a.m. Tuesday morning, lawyer W.M. Wilson calls Wallace at his home to report rumors of trouble. Wallace says he calls the police station and someone there calls assistant police chief Neal Elliott, the officer on duty. Wallace says he is told there’s only a disturbance at the Square caused by a Black woman, who was taken to the hospital. The Evening Chronicle, though, reports this call happened at 9:30, three hours earlier.

- Between about 12:30 and 1 a.m., Wallace gets a call from Dr. C.G. McManaway, who says his son saw a crowd gathering at Frazier’s Cafe on West Trade Street, between Church and Poplar streets. Wallace says he gets dressed, walks (about a third of a mile) to the cafe, sees no signs of trouble, then returns home. Perhaps the crowd has already moved on toward Good Samaritan Hospital, about two-thirds of a mile away. He says he asks two officers if there is anything to the rumors of trouble and that they say they haven’t heard anything.

- After 1 a.m., hospital attendants notice groups of men hanging around the hospital and people in the neighborhood hear men threatening McNeely. It’s also reported that residents hear people walking along nearby South Church Street. No one is named or quoted.

- Between 1:30 and 2 a.m., assistant chief Elliott says, he calls the hospital and officer C.E. Earnhardt, guarding McNeely, says there is no trouble.

- About 2 a.m., Sheriff Wallace gets a third call, saying there is going to be trouble at Good Samaritan. Wallace doesn’t say – and the Chronicle doesn’t report – who makes this call, nor why police aren’t alerted or don’t respond in the approximate 15 minutes left before the mob attacks. It takes only minutes for police to drive to the hospital, less than a mile away, so even as late as 2 a.m. there’s time to help. Wallace walks to the “scene of the reported lynching,” about a mile away from his home, but it’s too late.

2:15 a.m. Tuesday: The mob attacks

Officers Earnhardt and I.A. Tarleton are stationed at Good Samaritan with McNeely, who is shackled with leg irons on the second floor. The Chronicle later reports that police were there more to prevent him from escaping than to guard him.

The mob approaches. Both Earnhardt and Tarleton will first say there were 70 people or more. Estimates vary: Most newspaper accounts eventually report the mob as 25 to 35, or fewer.

Someone on the street calls out to speak with Earnhardt. It’s unclear who, and unclear how they know Earnhardt is there.

Buford Pickens, the nurse on duty, reportedly shouts, “You will not get in this house tonight.”

Then, a member of the mob breaks down the door.

Nurse Pickens, in the upstairs room with McNeely, will say about a dozen men enter the hospital, a gun is poked in her face and she is told to put her hands up. When the men burst into the room, Pickens says, they don’t know which man is McNeely – and McNeely points to another man, saying, “That’s the man you want.” That man responds: “For The Lord’s sake, I am not the one” – then the mob demands officers point out McNeely. Pickens says it is about two minutes between the break-in and the lynching.

Members of the mob strip McNeely of his nightshirt, and drag him naked down the stairs and into the streets.

At about 2:15, a volley of shots is fired. Reports vary as to how many.

McNeely falls, but is still alive, and the mob leaves.

2:30 a.m.: Police take McNeely to ‘The Tombs’

One of the two officers reportedly calls police. When other officers arrive they don’t take McNeely back inside Good Samaritan Hospital, though it’s just steps away. Instead, they drive him to the police station, called “The Tombs,” almost a mile away.

Wallace, still walking to Good Samaritan after hearing of trouble, says he sees the vehicle pass.

Police Chief Moore, who will say that he got no calls until after the lynching and that he had not heard “an inkling” of any rumors or plans of trouble, is called about 2:30 a.m. and goes to the station. McNeely is still conscious and Moore calls three doctors. Two come. It’s unclear if they attend to McNeely. Moore will say he counts seven wounds in McNeely’s body. Another report says there are 14 bullet holes.

The Observer’s front-page headline: “Joe M’Neely Is Shot By A Mob.” The story begins:

“What will in all probability prove to be the first lynching in Mecklenburg County occurred at 2:15 this morning when a mob of about 35 men stormed Good Samaritan Hospital and took therefrom the negro Joe McNeely, who last week shot Patrolman Wilson. The crowd threw him in the street in front of the door and riddled him with bullets. The crowd then dispersed on the instant.”

Deadlines leave the story incomplete.

“At 3:30 this morning,” the Observer story concludes, “McNeely was conscious and able to talk. He asked that the old bandage across his neck be pulled away so he could pray. It was said that his chance to recover was very slim.”

Joe McNeely dies at 5 a.m.

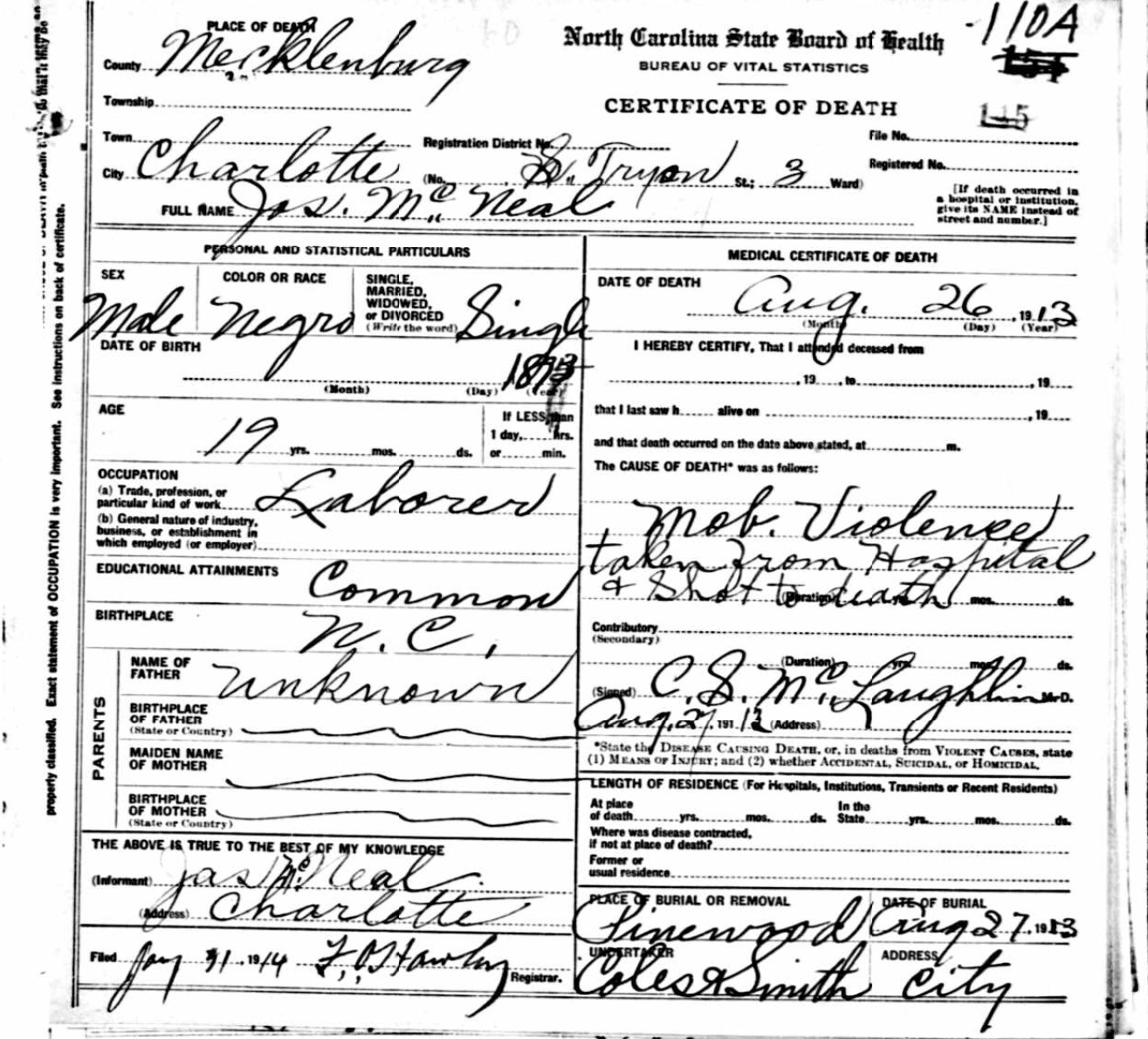

His death certificate reads “Mob Violence” with a second line: “taken from hospital & shot to death.”

In 1913, he is one of at least 51 Black men lynched in America.

At the lynching scene: What did newspapers know?

Newspapers carry detailed descriptions of the lynching, but where does the information come from – and when? Do reporters see members of the mob or witness the killing?

The Observer mentions “those who saw the occurrence” and quotes an unnamed “spectator,” who says: “We heard the clinking of the chains as they brought him down the stairs.” The paper doesn’t say who those people are.

How does the Observer know to report that a mob began to gather at 1 a.m.? Or to note that, with Good Samaritan Hospital located “in the center of a negro residential district … there had been well-grounded apprehension that serious race trouble would break out if the negroes learned of the plan in time to take a hand in it”?

How is the Chronicle able to give the following detailed description of the lynching?

“(The mob) was quiet, but purposeful… the entire program of death was carried out with as little noise and confusion as possible… There was but one volley and the crowd retired as it had come, walking away with as much precision and ceremony as though a funeral had been concluded.”

The News sums up: “The men of blood vanished like phantoms of the imagination.”

Did police search for the killers?

There is no indication that police launched an immediate search to find and arrest members of the mob, though they were reportedly alerted minutes after the shooting, when members of the dispersed mob might have still been near the hospital.

In contrast, in 1914, when two police officers are shot around 1:30 a.m., off-duty officers are summoned from their beds to locate the identified men who attacked their “brother officers” and within 90 minutes a dragnet is spread over the entire city, news reports will say. Four white men are arrested and Judge Shaw, fearing that a mob might attack, orders Sheriff Wallace and Police Chief Moore to move them to a prison in another city for their safety and to keep the location secret.

Later that day: Outrage by state, city officials, newspapers

Just hours after McNeely dies, daily newspapers begin to profess outrage and express confidence that “the people of the city feel too strongly to let (the lynching) go unavenged.” That sentiment is echoed by the governor, the mayor and city officials who all promise to find the murderers.

N.C. Gov. Locke Craig, one of the most prominent speakers in the 1898 campaign to restore white supremacy, which included threats of violence to Black people, says mob members will be “prosecuted and punished to the limit.” He says Charlotte officials “will not rest until the members of this lawless mob are brought to justice.”

Mayor Bland calls for a special meeting of aldermen (the equivalent of today’s city council) at 10 a.m. and offers a $1,000 reward; ads about the reward begin running daily in newspapers. Bland, “astounded” by the lynching, says the relationship between the races has always been friendly and there’s reason to believe that will continue.

Sheriff Wallace, who the previous day said the jail couldn’t take McNeely because there was no place to house a Black nurse, is “congratulating himself that the affair did not happen at the county jail, for which, in this event, he would have been held more directly responsible,” the Chronicle says.

Wallace promises to help find the killers.

Solicitor George W. Wilson, who is put in charge of the investigation, writes to Gov. Craig twice this day, asking him to add another thousand dollars to the reward: “I think that the Lynchers can all be found out if the matter is taken up in the right way and handled quietly.”

Two days later, Wilson will write the governor again, asking for additional money to pay “special secret service men” to search for the killers. He wants men not known in Charlotte, without allegiance in the community. “The policeman whom the negro shot was a very popular young man and this fact has made it very difficult to awaken interest in the apprehension of the guilty persons,” Wilson will write. (Note: These letters are available from the N.C. Office of Archives and History at MosaicNC).

Calls for security – at the white hospital, for the white officer

Though there are no reported threats, it’s decided additional officers are needed in case members of the Black community retaliate.

More men are sworn in and armed with Winchester repeating rifles and Colt pistols. Militia is called out and stationed around Presbyterian Hospital, where Wilson is recovering. They stay on guard there for days.

It’s reported that Myers Hardware Company, housed in the Central Hotel on Trade Street, was burglarized late Monday or early Tuesday morning. Initial reports say 10 to 12 pistols were stolen. The News will say the theft of pistols on the night of the lynching forces the conclusion that they were connected to the killing. But the shop’s owner tells the Evening Chronicle that he believes Black men, not the mob, came into the store through the back door, after McNeely was shot, and took 30 pistols and plenty of ammunition. He offers no explanation, other than what the paper calls “the manner the things were taken,” as to why he’s reached that conclusion.

Judge to grand jury: Mecklenburg’s name ‘stained with blood’

Just before noon on the morning of the lynching, Judge T.J. Shaw charges the Mecklenburg grand jury – already in its scheduled criminal court session – with finding McNeely’s killers. The Observer says his call to find “every man engaged in the slaying of Joe McNeely” is one of the most “stirring appeals … ever to be heard in the county courthouse.”

Newspapers quote Shaw:

“When the splendid name of such a county as Mecklenburg is stained with blood, we are stricken with horror. And gentlemen, there walks today on your streets 35 men, according to the accounts, who are actual murderers. What are you going to do about the horrible crime that has been committed in this city this morning, gentlemen of the grand jury?”

Shaw asks: Why would a mob commit such a crime? Then he answers: “Because they feel assured of protection and of safety from the hands of the law.”

Shaw criticizes police for not protecting McNeely: “What we needed at the time and on guard there was a South Carolina sheriff” with “courage and grit.”

The sheriff that Shaw singles out

Sheriff William James White, who Shaw is referring to, defended a Black prisoner against a mob just one week before McNeely was lynched. On Aug. 18, Will Fair was being held in the Spartanburg County jail, about 75 miles southwest of Charlotte, accused of assaulting a white woman. A mob, estimated to be more than 1,000 people, dynamited a wall and began to storm the prison. Sheriff White reportedly blocked them, saying, “Gentlemen, I hate to do it, but so help me God I’m going to kill the first man that enters that gate.”

The governor and mayor refused to help White, who created a diversion and had Fair moved to Columbia. Fair will be held for trial in September and found not guilty.

“If the sheriff of Spartanburg turned back a mob of a thousand, certainly the police of Charlotte, or even the two who stood guard at the hospital, could turn back a mob of less than fifty,” the Greenville News will write.

Charlotte police give reasons for not shooting

In Charlotte on Tuesday, the two officers assigned to guard McNeely give statements to an investigative group led by Solicitor Wilson, and to reporters.

The officers were outside McNeely’s room on the second floor when the crowd broke in and rushed up the stairs. Stories vary about whether Tarleton or Earnhardt had actually drawn their guns. Tarleton says he had his gun drawn but didn’t shoot: “It would only have meant that the hospital would have been riddled with bullets and I and Earnhardt and maybe the nurses that were behind us would have been killed instantly.”

Earnhardt estimates 40 men rushed the hospital wearing handkerchiefs and improvised masks. Other estimates say as few as six men entered the hospital. Earnhardt says he tried to close the door of the room where McNeely was being held, but the mob stopped him. One man held a pistol to his face, Earnhardt says, another to his temple, and two men forced him against the wall as McNeely was taken.

He says he had just pulled his gun but it, and a second gun, were taken away. He says he threatened, then pleaded with the intruders to leave. The Observer will report Earnhardt says he could have shot but “knew the two men could stand no chance against such a mob and as a matter of saving his own life he had to behave himself.”

Tarleton says he was seated in the second-floor hallway when he saw three men at the hospital gate. Others arrived. He says he met them at the stairs: “At the point of the pistol I surrendered my gun… About six men kept us covered.”

Tarleton says he heard several expressions while making his rounds on the city streets Saturday that McNeely should be killed, but didn’t consider it important enough to report. Earnhardt says he had heard only wild rumors of violence and had not anticipated trouble.

Both officers insist they can’t identify anyone, though it is reported that not everyone wore masks and some had masks barely covering their faces.

Nurses tell their version; matron says never again

Nurse Buford Pickens, one of three Black staff members to testify, says she had a gun poked in her face and was told to put her hands up. She says she can’t describe any of the mob.

Elizabeth Miller, hospital matron, says she was in her first-floor room when a police officer ran downstairs to call for help. “He got to the foot of the stairs when the mob rushed in. He was ordered to throw up his hands and his pistol taken from him … I opened my door to see what was the matter and someone called out, ‘Shut your door.’ ”

Miller also says, “We do not have to take in cases like McNeely, but we do so in the cause of mercy… I shall strongly oppose in future any criminal wounded being brought here. The city will have to find a place for them. We had a night of terror and there is no need for us experiencing such again.”

It’s reported that nurse Pearl Wallace, off-duty, was in her room and told to stay there. The News says the matron and nurses “bore themselves with remarkable nerve” during the attack.

Opinion writers’ version challenges police, presumes McNeely guilty

“It seems incredible that 40 men should have passed by hospital attendants and two policemen without any trace of identification being established, but early today there seems to be no clue as to any identity of any member of the mob,” the News writes.

Though Wilson was alive and the penalty for assault with a deadly weapon was not death, the opinion writer claims that McNeely “richly merited death by law. If the law had been allowed to take its course the negro would have paid for the crime with his life, and then there would not have been the stain of blood on the hands of members of the mob…”

But it also says: “Judging by past records, there was no certainty that this negro would be executed and this in fact may have weighed with those who took the matter in their own hands.”

(The day before the shooting, a letter to the News had claimed that of 41 people charged with murder in three and a half years, only one person was executed.)

In its own piece, headlined “Charlotte’s disgrace – the remedy,” the Chronicle writes on the opinion page that the two officers failed in their duties: “Fear of their own precious lives was no excuse. They were sworn in to uphold the law at any cost, and they did not do it.”

Wednesday, August 27

Observer says Charlotte humiliated

The Observer writes that Charlotte has been “humiliated as never before” and questions whether police had let the mob know they would allow McNeely to be lynched:

“We do not at present undertake to say whether at least morally positive assurance of police non-interference had been received. It is certain that at least the police headquarters (as also the sheriff and the night newspaper reporters) were circumstantially informed from several quarters of a lynching afoot, and that the newspaper men, believing, later guided themselves by the story to the spot almost on the moment while the officers could not be gotten interested.”

The Observer questions why officers didn’t identify mob members who they probably knew, saying the killers wore masks that didn’t completely cover their faces, or no masks at all. The newspaper also says: “We do not doubt that (Sheriff Wallace) was willing to do his duty. He simply had his eyes so closed to the danger that he could not see.”

The Charlotte News writes: “It has become an unwritten law, or fixed belief, that there never would be (a lynching). Possibly the lynchers acted upon the knowledge of this belief and took the city as it were off guard.”

And the Chronicle quotes an unnamed member of the city’s executive board as saying, “Sheriff Wallace, I am informed, was notified in abundance of time to have prevented this trouble.” (A day later, the Chronicle will say facts of the case “exonerate Sheriff Wallace.”)

The same unnamed official says he understands the officers’ lack of action: “It is not the part of the average white man to shoot another who has come to get vengeance on a negro who is deserving of extreme punishment.”

Judge criticizes officers: ‘A toy pistol in the hands of a child’

Judge Shaw clarifies his Tuesday comments: “Yes, I meant a criticism of the officers in charge of the man. Pistols in the hands of two officers who do not intend to use them are worth about as much as a toy pistol in the hands of a child.”

Or, as a Sumter (S.C.) newspaper had put it just two weeks earlier: “We have yet to hear of a jail being stormed or a sheriff overpowered when the jail was defended by an officer who was prepared to kill or be killed.”

That comment came after a mob stormed a jail in Laurens, S.C., on Aug. 11, then hanged and shot Richard Puckett, a Black man accused of trying to rape a white woman. She had not been able to identify him. Instead of being outraged, S.C. Governor Coleman Blease was quoted as saying: “The good white people of Laurens know how to defend their women.”

Joe McNeely buried; militia on guard at hospital

Joe McNeely’s body is taken by Coles & Smith undertakers, placed in a pine box and quietly buried without a marker at segregated Pinewood Cemetery.

Extraordinary care is taken to protect Wilson. Squads of militia are stationed around Presbyterian Hospital. The Observer says they are “men whose nerve was not questioned and who were sufficiently equipped to stand off a mob of almost any size.”

Hardware stores and pawn shops are ordered to sell no arms or ammunition. Sales of alcohol and beer are temporarily banned.

It is reported that the city might bring in outside detectives to search for mob members, to offer a fresh perspective.

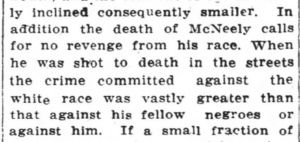

Chronicle: White race most harmed, not McNeely

Chronicle: White race most harmed, not McNeely

A Chronicle piece claims it is not the murdered Joe McNeely who was most harmed by this lynching: “The death of McNeely calls for no revenge from his race. When he was shot to death in the streets the crime committed against the white race was vastly greater than that against his fellow negroes or against him.”

N.C. newspapers criticize Charlotte. A Greensboro Daily News editorial says the Observer “felt justified in the prediction that there never would be a lynching in Mecklenburg. Now, the community shelters a mob of the blood-thirsty. Mecklenburg has been shamed and has shamed North Carolina.”

The Greensboro Record: “It was a case where ‘Silence’ gave consent. This is plain. The officers didn’t know and didn’t want to know; they kept from knowing; they could not hear, neither could they see. When they discover the names of the lynching party, let us know …”

The Robesonian: “It is inconceivable that it could have happened as it did without the connivance of the police.”

Thursday, August 28

Conflict of interest: Police help newspapers get subscriptions

As newspapers write about the actions of the police, local police officers are competing in a contest to win a new $900 Roadster by soliciting subscriptions and renewals and collecting money for the Evening Chronicle and the Observer. “Many hundreds of dollars had been turned in” by police and other city workers, the Chronicle writes. Officer Wilson led the contest among police until he was hospitalized and unable to sell subscriptions.

As newspapers write about the actions of the police, local police officers are competing in a contest to win a new $900 Roadster by soliciting subscriptions and renewals and collecting money for the Evening Chronicle and the Observer. “Many hundreds of dollars had been turned in” by police and other city workers, the Chronicle writes. Officer Wilson led the contest among police until he was hospitalized and unable to sell subscriptions.

Also:

Under the Chronicle headline “Will Demand Resignation Of The Two Hospital Policemen,” Mayor Pro Tem T.L. Kirkpatrick says that unless the executive board investigating the lynching takes action to remove the officers, he will bring it up to the aldermen. But the officers will not resign and no reports suggest they are reprimanded.

The Chronicle is the only local newspaper to keep the story on Page 1 by Thursday, announcing that the grand jury is preparing to bring in outside detectives to help with the investigation. The Observer’s Page 2 story includes the headline: “Conditions In The City Are Perfectly Quiet In All Quarters … Only Good Feeling.”

Friday, August 29

Observer: Reward not worth the consequences

The Observer reports that the $1,000 reward money has not created “a ripple of interest” and asks the governor to add $1,000 more (he never does). But even that, the paper notes, might not be enough.

The Observer reports that the $1,000 reward money has not created “a ripple of interest” and asks the governor to add $1,000 more (he never does). But even that, the paper notes, might not be enough.

It’s possible only someone in the mob could identify others, the Observer says, and he’d need to be offered immunity. But a reward of $1,000 or even $2,000, the paper says, would not be worth the consequences. Anyone taking the reward would have to “balance … the good time he could have with the $1,000 or $2,000 against the hatred of those with whom he made a compact …”

The Observer says outside detectives might be brought in and would be effective in finding the killers.

Also:

In a second instance of the rare times when a newspaper publishes a comment, unnamed, from a Black person, the Observer writes: “A negro woman living near the hospital spoke sarcastically of the manner in which some members of the party fired into the air … It is probably because some of the mob men revolted at the last moment at the repulsive act which they had come out to do.”

The outrage over the lynching three days earlier is fading in Charlotte, says the Chronicle, and it “does not appear likely anything will be done.”

Grand jury disbands, zeal to identify killers ‘dying away’

“Grand Jury Has Found Nothing,” the Chronicle will say Saturday. The grand jury’s final report doesn’t mention the lynching nor McNeely, much less identify any mob members.

“This is taken to mean that the agencies which are supposed to ferret out crimes in this community are gradually becoming exhausted.” Many witnesses who “might have knowledge of the occurrence” were summoned, the Observer says, but didn’t help identify the killers.

“This is taken to mean that the agencies which are supposed to ferret out crimes in this community are gradually becoming exhausted.” Many witnesses who “might have knowledge of the occurrence” were summoned, the Observer says, but didn’t help identify the killers.

The 18 white men on the grand jury: Foreman T.J. Renfrow and Martin Oehler, V.Y. Brawley, G.V. Keller, James R. Henderson, W.C. Neal, J.A. Boyles, E.C. Grier, L.A. Stutts, T.J. Orr, John G. Weber, J. Mack Holbrook, J.H. Hall, J.M. Spoon, H.A. Caldwell, J.N. Wilson, W.L. Ewart and W.M. Tye.

The Greensboro News: “The Charlotte Aldermen are said to be indignant at the publicity given the little soiree held in their town the other night. No doubt so are the lynchers and the policemen who were ‘overpowered.’ But murder will out, even if it be done in Charlotte.”

A Raleigh News and Observer editorial criticizes Charlotte City Council members for complaining about the amount of “publicity” that newspapers are giving to the lynching and for supporting police officers who failed to do their job.

Sunday, August 31

Star of Zion: Police should have expected trouble; officers failed

The Chronicle reports that the Star of Zion, a Black-owned newspaper, says the following (note: The Star of Zion, a paper of the A.M.E. Zion Church still in existence, did not publish daily, and archives are incomplete nationally, so this excerpt has not been verified in original form):

“Joe McNeely was a worthless negro of the lowest type and there is no sympathy expressed for him by the colored people of this community and yet there is not a reputable negro in this city who does not resent the cowardly murder of Joe McNeely by the hoodlums who broke down the door of a hospital in which helpless women watched over the bedside of many sick and defenseless. Charlotte is disgraced, humanity is outraged. Speaking for the negro citizens of the city, we are free to say that it is not believed that the decent white people of this community have any sympathy for the lynchers. We believe everybody despises them and resents their infliction of this dastardly crime on our city.

“Prominent negroes when consulted are unanimous in the advice to wait and trust the authorities to discover and punish the mob. We find no cause to blame Sheriff Wallace, but we do charge the outrage upon the police force who had reason to expect trouble and two members of that force failed signally to do their duty.”

The Star of Zion is also quoted in the Observer referring to Jane Wilkes, a white woman who raised funds along with Black churches to open Good Samaritan Hospital in 1891:

“And Mrs. Jane Wilkes, at whose funeral a few short months ago negroes bore flowers in tribute to a noble life, what does she, looking down from heaven, think of a mob breaking into the hospital she founded and being permitted by two officers to do brutally to death a wounded negro?”

A Gaffey (S.C.) Ledger editorial mocks the “bravery” of the officers assigned to guard McNeely: “There will be a faint show of investigation, some men will swear to a lot of lies in order to shield some other men and the whole thing will be dropped.”

Mayor Bland says it is no longer necessary to keep militia on guard duty at Presbyterian Hospital. The embargo on liquor and beer sales is lifted. The Chronicle again calls for outside detectives. But help is never brought in.

Five days after the lynching, the Observer says: “It is reported that the detectives are hard at work on the case, but to the truth of this it is impossible to say.”

Monday, September 1

Another call for investigation help

Solicitor Wilson writes the governor again, saying he has an outside investigator he can bring in but needs money to pay him. He writes: “This lynching was done by a very small crowd, not exceeding ten men and they will be hard to detect, unless the effort is made along the right lines.”

Two days later, on Sept. 3, Wilson writes Craig again, offering to come up to Raleigh to talk in person.

On Sept. 5, Gov. Craig writes Wilson back: “Come to Raleigh to see me. The sooner the better.”

Saturday, September 6

Investigation fades further; state newspapers mock Charlotte

There is little news in the papers about efforts to find the men who lynched Joe McNeely. State newspapers continue to criticize Charlotte.

The Durham Herald: “If you want to find out how public opinion stands regarding lynching just start an investigation in the hope of apprehending a set of lynchers.”

The Statesville Landmark: “The Charlotte newspapers assumed that a lynching was impossible in Mecklenburg and at least one of them boasted of their superiority in that respect. Subsequent events showed that there are the same sort of folks in Mecklenburg that are found in other counties.”

Saturday, September 13

White officer recovering

In his first interview since being hospitalized, Wilson tells his version of the shootings to the Observer. He says Chief Moore told him to arrest a “cocaine-crazed negro” and that as he arrived at the scene on a motorcycle he was shot several times. Wilson said he then shot McNeely and beat him with his blackjack.

Wilson is recovering and expected to leave the hospital in about a week. The paper says Wilson has not seen newspapers while in the hospital, nor has he been told about the lynching of Joe McNeely. Wilson says he hopes McNeely leaves town and that there is no more trouble.

Wilson will return to his job as a Charlotte police officer and later move to Danville, Va. A 1920 Lynchburg News & Advance story announcing his appointment as special agent for the Southern Railway will say Wilson had been shot at no less than 13 times in the line of duty, and hit 11 times, including in Charlotte by a “cocaine crazed negro.” He will die in 1927 of damaged lungs.

Monday, September 15

Solicitor: Investigation delay is hurting

Solicitor Wilson writes Gov. Craig, still seeking an outside investigator: “I have not heard anything further in regard to the man who is to take up the Charlotte matter… You will pardon me for calling your attention to it again, but I think we might lose something by too much delay.” It’s been three weeks since the lynching and 19 days since Wilson first requested an outside investigator to help find the killers.

Two days later, Craig will say he’s sending someone from the insurance office to investigate.

Saturday, September 20

Hospital adopts policy

Good Samaritan Hospital’s board announces a new policy: No person charged with a violent crime shall be admitted into the hospital except for temporary or immediately necessary operations or treatments, and the person must be immediately removed after treatment.

The board adds that the chief of police or sheriff should provide a “sufficient number of brave men” to protect the patient and hospital from unlawful assault and trespass.

Saturday, October 4

Outside investigator not working out

Solicitor Wilson writes Gov. Craig that the insurance investigator isn’t working out: “Mr Jordan (the investigator) is very capable, but we will have to have a man who is unknown… (Jordan) is not in position to get anything more than we have in the case. He is well known and is in the employ of the state. I should be glad that you would write me what you think of the matter.”

It’s unclear if there is additional correspondence between the two men.

Sunday, October 12

'We do not know'

The News, asked what was being done to apprehend Joe McNeely’s killers, replies: “The lynchers are still at large and what is being done now to apprehend them we do not know.”

The next lynching

'Charlotte lynching, untouched of justice, has borne fruit...'

Prior to the lynching of Joe McNeely in 1913, there had been no documented lynchings in North Carolina since 1906.

That August, Black men Nease Gillespie, his son John Gillespie and Jack Dillingham were seized from the Rowan County jail where they were charged with murdering a Salisbury white farmer, his wife and two of their children. Newspaper reports said the three men were hanged and riddled with bullets. A crowd estimated at more than 3,000 people watched, then collected pieces of the men’s clothing as well as their fingers, toes and ears.

Newspapers across America reported the gruesome killings and called for justice. The reported leader of the lynch mob, George Hall, was convicted and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Hall’s conviction was the first in North Carolina of anyone involved in a lynching, it was reported.

That punishment, it was believed, ended documented lynchings in North Carolina for seven years – until McNeely was lynched. Newspapers around the state called for arrests again. “It is safe to say that even if one of the Charlotte lynchers goes to the penitentiary,” the Greensboro Record said, “there will not be another lynching in the state in another seven years.”

But there were no arrests. The next confirmed lynching came just five months later: Jim Wilson was hanged in Johnston County on Jan. 27, 1914, before about 1,000 people, none masked.

“The Charlotte lynching, untouched of justice, has borne fruit in one other. That is one too many,” the Greensboro Daily News wrote.

The Statesville Landmark wrote: “When the shameless Charlotte lynching took place some months ago, the authorities, including Gov. Craig, asserted somebody must be punished. Nothing was done. Hence the Johnston County folks, justly indignant on account of the brutal murder of a woman, felt perfectly safe in killing a negro, in open day and undisguised. Lawlessness grows by what it feeds on. This time Gov. Craig doesn’t say somebody shall be punished. Experience has shown him they won’t be.”

In the seven years after McNeely was killed, 13 lynchings were documented in North Carolina. There might have been more.

Who was Joe McNeely?

We know little of Joe McNeely before August 1913: no photographs, few details of his life. Daily newspapers rarely wrote about Black people except when they were accused of crimes, convicted or died in a violent or unusual way.

A Chronicle story on the day of the August 1913 confrontation said McNeely was known by police “through a number of minor misdeeds” and cites an October 1912 arrest (previous stories say he was sentenced to a year on a chain gang for assault, which was dropped to six months on appeal). Other earlier stories say he received a three-year sentence to a chain gang for stealing a bike (one year) and for forcible trespass (which he denied).

As part of the 2019 exhibition “It Happened Here” at the Levine Museum of the New South, historian J. Michael Moore wrote that between 1900-1920 “at least 90 percent of the prisoners in the camps in Mecklenburg County were African American. This probably reflects both a bias in the arrest and prosecution of Black men and an increased likelihood that Black defendants were too poor to pay small fines or costs in the case of petty offenses.”

Moore wrote, “The county prison camps and their chain gangs were central to the criminal justice system of North Carolina … The prisoners, usually chained and shackled, provided the heavy labor for creating and maintaining the road system of the state, which was considered an essential investment in the development of the state economy …

“… Prisoners in Mecklenburg County’s camps endured the worst conditions of any camps in the state of North Carolina. The horrible conditions in the county camps would be revealed to the world in 1935, when the camp supervisor, the county physician and several camp guards were charged and tried for the torture and maiming of two young Black convicts. The two men, Woodrow W. Shropshire and Robert Barnes, both had their feet amputated after getting frostbite while being held in solitary confinement.” (Note: None of the men charged would be found guilty).

Jim McNeely, an older brother of Joe’s, was sentenced to chain gangs multiple times, according to newspaper stories. Then, in 1908, he was shot and killed by chain gang guards who said he was trying to escape. An unsigned musing on the Observer editorial page quoted a “well-known Mecklenburg farmer” saying: “I look for the grand jury to take up the case … There are many people who know the circumstances of that homicide that would like to see it looked into a little further. The convict was a negro but we claim to be a Christian people. That boy should not have been killed.”

By 1915, Robert, another older brother of Joe, was working in a Charlotte restaurant and younger sister Mary had married and lived with her husband on Tryon Street, next door to parents Fannie and John. When John died in 1917, the remaining McNeelys appear to move to Yonkers, New York. Fannie died there in 1928, Robert in 1935 and Mary in 1985.

Do you think you might be a relative of Joe McNeely? Reach out to us at charmeckremembers@gmail.com.

Current site of 1913 lynching: Inside stadium

Historian Moore figured out that the site was on the Bank of America stadium property. While doing research for the 2019 Levine exhibition, he used historic street and fire insurance maps, photographs of the hospital and descriptions of the lynching to triangulate the location.

Good Samaritan, once at 405 W. Hill St., near the intersection with Mint, was torn down, Mint rerouted and Hill interrupted in building the stadium. Further research by Moore determined a closer approximation of the site: near the southwestern corner of the stadium bowl, where the field meets the stands.

Lynching unmentioned, for decades

After 1914, the lynching of Joe McNeely will not be noted again in the Charlotte Observer or News until his name appears as an item in a 1933 Observer “Looking Backward” column under the heading “20 years ago today.”

The killing is mentioned again, 85 years later, in an Observer 2018 story about the Equal Justice Initiative’s Remembrance Project and the importance of remembering that the lynching of Joe McNeely happened here.

The Remembrance Project worked with the city and Tepper Sports & Entertainment on a soil collection at the site of the lynching; read about that and see photographs here. The city and Tepper Sports & Entertainment have agreed to erect a historic marker on stadium grounds. Get updates by signing up at the “Stay Connected” box at the bottom of this page.

Read for yourself

Want to look at entire newspaper stories, or the whole range of them, for yourself?

If you have a library card, you can look at all stories from the Charlotte Observer — the News is not archived there — by going here, then Charlotte Observer, then searching: You can search by names and other words, and limit searches to a particular time period.

Newspapers.com has the News and other papers, but it’s a paid service; it may offer a free trial.

If you’re interested in genealogy or want help researching your own family history, the library has a genealogy librarian: Danielle Pritchett is available via email at apritchett@cmlibrary.org or through the Carolina Room at carolinaroom@cmlibrary.org. She has also conducted classes at library branch locations.

Gary Schwab is a freelance journalist who was a Charlotte Observer editor and writer for 30+ years, and an associate producer/consultant for the documentary “A Binding Truth,” which was inspired by stories he wrote.

This story is drawn from newspaper archives and genealogical documents; the wide-ranging and ongoing work of historians Dr. Willie Griffin, J. Michael Moore, Dr. Pamela Grundy and Dr. Tom Hanchett; and research assistance from Shelia Bumgarner, Tom Cole and Meghan Bowden of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Public Library, and Helen Schwab; editing assistance from Harry Pickett.