It's time to face our past: Stories of lynchings let us see Charlotte for what it has been.

By FANNIE FLONO

By the time 22-year-old Joseph McNeely was lynched in Charlotte in 1913, he was the 149th documented death in North Carolina at the hands of white vigilantes in 48 years. That was roughly three a year since the Civil War ended in 1865.

McNeely’s murder was the first documented lynching in the Queen City. He was among at least 51 Black men to have died nationwide that year at the hands of such mobs.

The only other documented lynching in Charlotte would take place 16 years later in 1929. Willie McDaniel, a 22-year-old tenant farmer, was found face down in the woods with a broken neck after an argument with the white man who owned the farm where McDaniel and his wife, Sallie, lived and worked.

That’s not to say other lynchings didn’t happen. Neighbors of McDaniel reminded authorities in 1929 that another Black man had been found murdered in their community years earlier, and the case never resolved.

Still, Charlotte leaders expressed surprise that such an atrocity could happen in the Queen City where they viewed Black/white relations as cordial. That was a statewide sentiment. N.C. historian Hugh Lefler said in his widely used 1959 textbook, “North Carolina History, Geography, Government”: “Nowhere in the South did whites and negroes live together more peaceably than in North Carolina.”

That wasn’t the truth. White animus against Blacks was real and ever present in North Carolina. Too often violence was the result. The last documented N.C lynching took place in 1946, the state’s 170th.

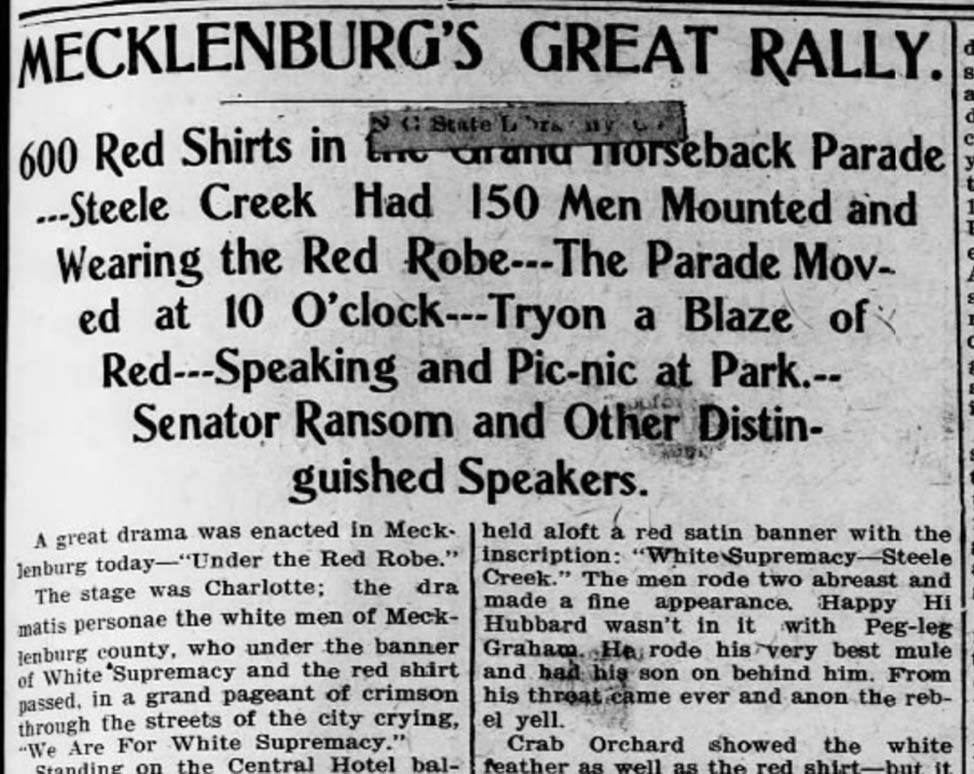

In 1900: A white supremacy parade down Tryon

Charlotte made its sentiments plain in July of 1900.

About 600 men in red shirts paraded down Tryon Street, some on horseback, hoisting signs with racist slogans proclaiming “White Supremacy.” Leading the group were Police Chief W.S. Orr and former vice-mayor Robert Heriot Clarkson, who later became a N.C. Supreme Court Justice. As many as 5,000 watched.

As the city grew, so did racial violence and discrimination. By 1903, city laws restricted Black access to transportation, parks, health care and schooling. Most white employers refused to hire Blacks except for domestic and farm work and service jobs.

By 1920, many Blacks had had enough, and fled. Charlotte’s Black population dropped from 40 percent to 31 percent.

McNeely’s 1913 lynching happened against that backdrop.

Joe McNeely

McNeely was one of eight children born to Fannie, a laundress, and John McNeely, a laborer, who had moved to Charlotte from nearby Union County. When he was killed, McNeely was one of only three siblings still alive. One brother, James McNeely, known as “Chicken Jim” for his propensity to steal chickens, was killed by a prison guard in 1908.

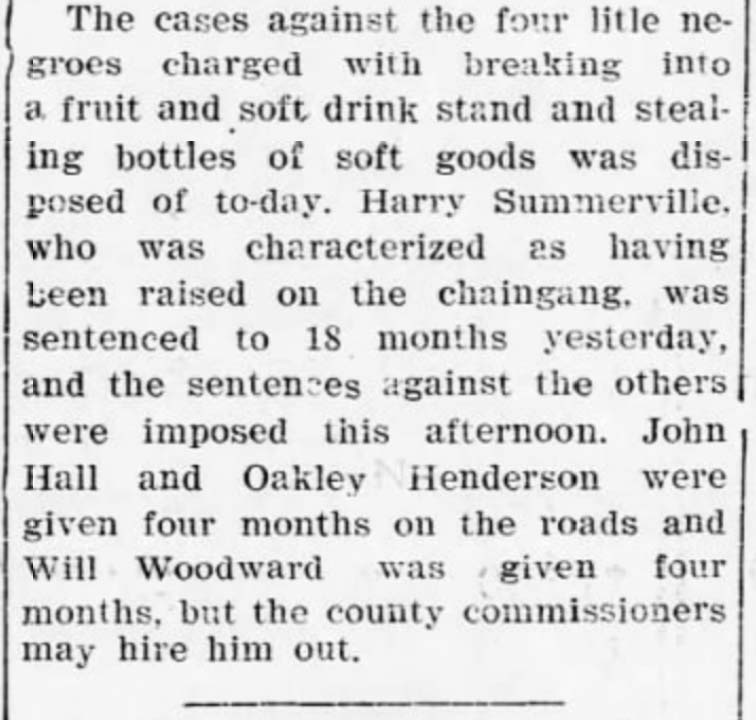

Joe McNeely had known his share of legal trouble, too. He was arrested for a fight in 1907 and was one of 41 prisoners living at a prison labor camp to the northeast of the city in 1910.

McNeely’s legal troubles followed a familiar pattern. After the Civil War, many Black men wound up in jails and prisons, often for petty offenses. Historians say it was the South’s way of re-enslaving Blacks, setting up a system that provided free and cheap labor.

North Carolina’s prison labor camps built on that premise. During the time McNeely was imprisoned, the inmates provided the heavy labor for creating and maintaining the N.C. road system, essential in the development of the state’s economy. Nearly 9 out of 10 men convicted of crimes were sent to prison camps. And in Mecklenburg County, at least 90 percent of the prisoners in labor camps were Black, most imprisoned for petty offenses. All but three of the 41 listed on 1910 Census records with McNeely in the prison camp were Black. Many were teens — the youngest 14.

McNeely had also been arrested for burglary, larceny and, in 1912, assault, after shooting a woman in the leg – though the woman agreed with his claim it was in play, and an appeal dropped his sentence to six months.

The shootings

His offense in 1913 was more serious. He was charged with shooting a police officer. According to news accounts, McNeely shot Charlotte police officer L.L. Wilson after Wilson responded to a call about a man brandishing a pistol and threatening people on South Tryon Street. Reports said McNeely fired at least three times at Wilson, who was seriously injured in the abdomen and jaw. Wilson reportedly returned fire, injuring McNeely in the groin and abdomen. He then beat McNeely in the face and head with his “blackjack.” The police chief and other officers found both a few minutes later, Wilson bleeding badly and McNeely unconscious in the road.

Officer Wilson was rushed to Presbyterian Hospital. McNeely was eventually taken to nearby Good Samaritan Hospital, the hospital for Black people, where he underwent surgery. Fannie McNeely told a reporter that her son Joe had been “sick with fever” for two weeks and had slipped out of the house the morning of Aug. 22, 1913, with a gun. Another account said McNeely had been drinking whiskey that morning and that he later acquired and used cocaine.

McNeely was recovering at Good Samaritan four days later, in leg irons and under police guard, when masked men pushed past the guards and nurses, stripped McNeely and dragged him naked down the stairs and out into the street. More men, many masked, were in waiting. They riddled McNeely with bullets and left him for dead. Police took him to the jail, not a hospital, where he lived for two more hours.

Charlotte leaders bemoaned the killing and offered a $1,000 reward for information about the perpetrators. But no one was ever arrested. Talk of a lynch mob forming was well known, but police took no precautions. So, some suspected the police were complicit.

The final determination about the assailants was “persons unknown.”

Officer Wilson recovered and returned to policing.

Willie McDaniel

By 1929, that kind of mob violence had decreased nationwide. Willie McDaniel was just one of seven publicly known lynchings across the country that year.

By 1929, that kind of mob violence had decreased nationwide. Willie McDaniel was just one of seven publicly known lynchings across the country that year.

And some Black people were making significant progress. In 1915, a pamphlet called “Colored Charlotte” took note of the city’s “best achievement” by African Americans: Black people owned 805 homes, 144 businesses and over $1 million in taxable property. There were 39 public school teachers, 55 carpenters, 80 bricklayers and plasterers, and proprietors of 24 Black-owned grocery stores.

Those changes dueled with the big challenge Charlotte’s Black residents continued to face — white resentment at Black progress and the violence and terrorism that often resulted.

McDaniel’s murder followed a financial dispute all too common as that resentment grew, and segregation and discrimination hardened: White people refusing to pay Black people for work.

According to news accounts, McDaniel and his wife were tenant farmers on the farm of Mell Grier in the Newell district, northeast of Charlotte. They had just moved there in January of 1929. Six months later, on June 29, McDaniel got into an argument with Grier after Grier refused to pay him for “some hauling” and his wife for blackberries she had picked for Grier.

Eyewitnesses reported that after the argument, McDaniel started to drive off in his wagon. But Grier said he would have no “muttering” he couldn’t hear and started after him. Witnesses later testified that Grier threw a rock at McDaniel, one saying the rock knocked his hat off. McDaniel then jumped down from his wagon and the two grappled with each other. Grier went back into his house and returned with a gun. Witnesses said Grier’s young niece prevented him from firing on McDaniel by bumping the gun when Grier aimed it at the fleeing man.

Grier gave chase, later explaining that he was attempting to bring McDaniel back to “feed the mules,” not to hurt him. The next morning, a Sunday, a young Black girl found McDaniel’s body on Grier’s property in the woods, near his cabin. He had a broken neck and marks on his neck and wrists, and there were indications he had been moved to where he was found.

The police did little to investigate the case. Officers took Grier’s word that he didn’t do it, nor knew who did. Jim Edmonds, who shared the cabin with McDaniel, saw Grier searching for McDaniel and said Grier was the last one seen with him. Edmonds asked Grier point blank if he had anything to do with McDaniel’s death. Grier said cryptically: “Uncle Jim, I didn’t do it. He brought it on himself.”

That didn’t prompt further questioning of Grier. Instead, Police Chief Vic Fesperman arrested and jailed six of the Black tenant farmers, including McDaniel’s widow, charging they knew more than they were telling. Police even suggested a Black gang had done the killing. Friends of McDaniel, in the meantime, had hired a white lawyer, Jake Newell, to investigate what happened. At Sallie McDaniel’s behest, he petitioned for the body, which had been buried without the widow’s knowledge, to be exhumed and examined for gunshot wounds after stories circulated that he had been shot. No bullet wounds were reported found and the coroner confirmed that McDaniel died of a broken neck.

Newspaper reporter LeGette Blythe further investigated and found a spot on the Grier farm where a tree seemed to have been used for the lynching. He also discovered drag marks on the ground indicating the body was moved. But an inquest determined McDaniel’s death was by “a person or persons unknown.” In October, Charlotte’s Black workers marched in protest.

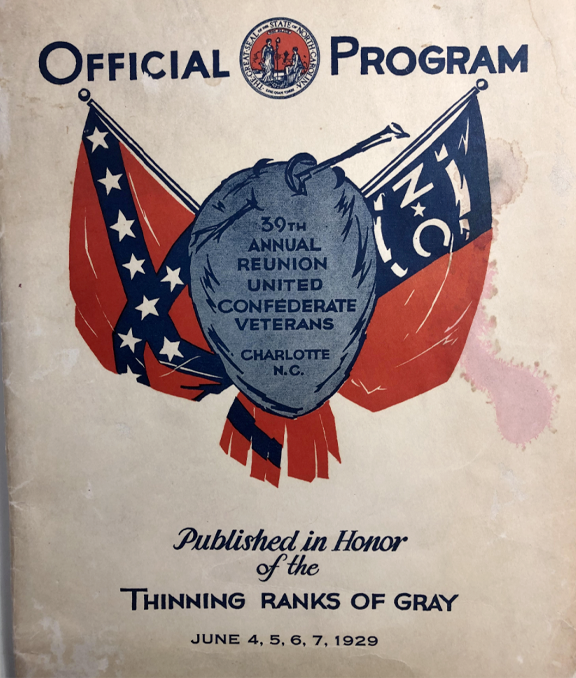

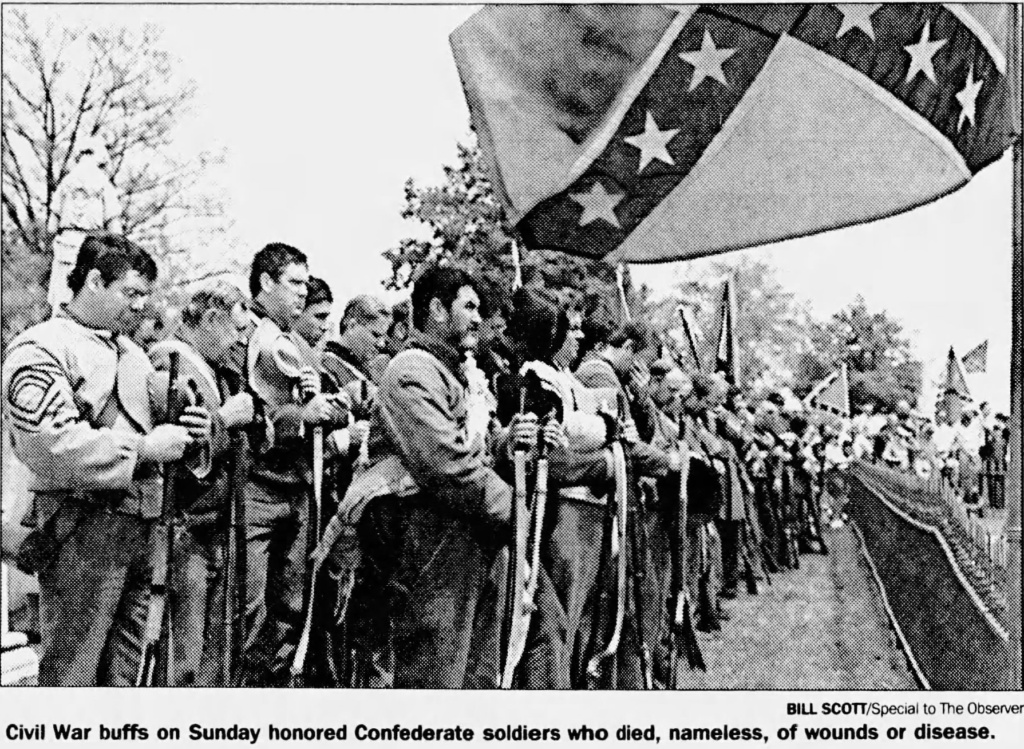

McDaniel’s murder came just three weeks after some 75,000 people (crowd estimates varied) gathered in Charlotte for the annual reunion of Confederate veterans.

That reverence for the Old South helped fuel actions, even violence, to keep Black people as second-class citizens.

Charlotte’s affection for the Confederacy and what it stood for continued for years. In 1958, city officials temporarily renamed Trade Street as Confederate Boulevard, and allowed a fake “secession” to take place in front of the Mecklenburg Courthouse as part of a commemoration.

In 1996, they allowed a Confederate Parade down Tryon Street.

Today, most Charlotte residents would be surprised to learn that in the city many think of as progressive, at least two people were lynched, or that city leaders approved a public celebration of the Confederacy just 28 years ago.

History is a powerful teacher if we know and acknowledge it. It is time.

Fannie Flono is a retired award-winning journalist. She worked for years at the Charlotte Observer, was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard studying the impact of race and class on public education, serves on Charlotte’s Legacy Commission and the boards of Read Charlotte and the Charlotte Museum of History, and is the author of “Thriving in the Shadows: The Black Experience in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.”